The etymology of procrastination is rooted in putting something off until tomorrow. The curse of procrastination lies in the perpetual delay of tasks, as tomorrow never truly arrives. It is always a day away, and with it, the promise of a task completed.

This is a tale of something I have put off until hundreds of tomorrows.

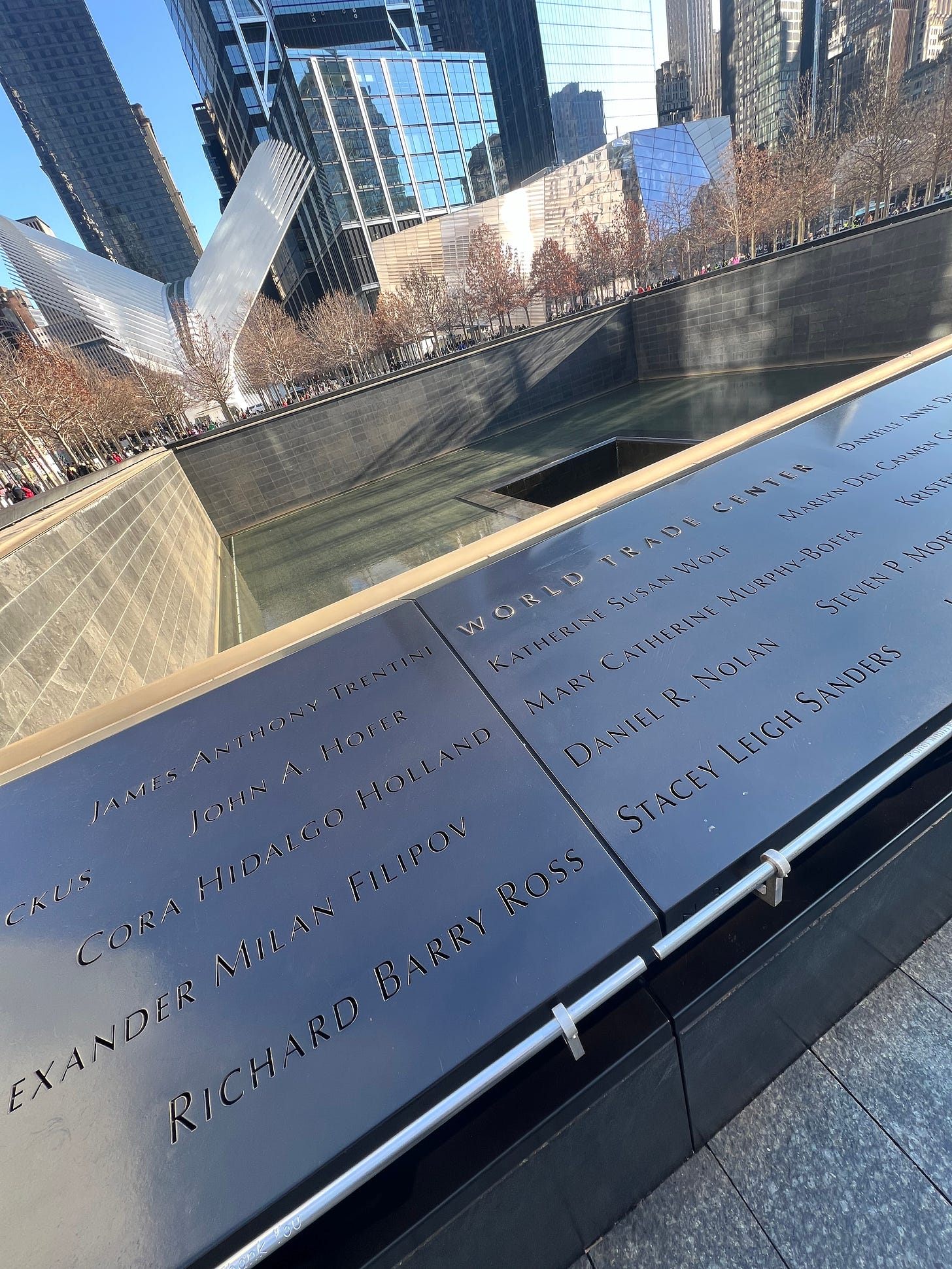

Every time I go, I start in the same two places. Places I remember from over a decade ago. Places that were simply ideas, then construction sites, and finally, a memorial to those killed on 9/11 and 2/26. This place is the 9/11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan. There, two fountains sit in the footprint of the Twin Towers. Around them, inscribed into bronze, are the names of those killed in 1993, when the World Trade Center was first attacked. Those six names are joined by the thousands killed less than a decade later in 2001.

One spot is the name of a man I knew. On the south side of the south tower’s footprint, you will find the name Roko Camaj. Roko worked at the trade center in the most amazing way. He would go to the roof and over the side to clean the windows at the top of the towers by hand. I got to know him less than a year before the attacks of 9/11. I worked on a documentary short about his life and high-flying career. He was a lovely man who genuinely seemed happy for every moment.

My next stop is at the names of two people I did not know. Their names are together in the bronze around the memorial's north pool. They are Richard Ross and Stacey Sanders.

In a place layered with heartbreaking stories, this is one that routinely occupies my mind. As a child, Stacey was best friends with Abby Ross, and Abby’s father was Richard. On the morning of 9/11, he boarded Flight 11, which hit the north tower where Stacey worked. Their names are not beside each other by chance. In locating each name, the memorial sought to achieve “meaningful adjacency.” Around both memorial pools, over 1000 names are adjacent to each other physically, but the people are connected in far deeper ways.

The first time I learned anything of this idea, I was sworn to secrecy, a pledge I happily took. It was in 2010, and I had been given the job of gaining access to the WTC site for the purposes of documenting the rebuilding as the 10th anniversary of the attacks approached. Then, only 1 WTC could be seen from the street; a 10-foot high fence obscured the view and fed the public’s belief that nothing was happening, that the rebuilding was all talk.

But that wasn’t the case; the fence and very publicity-shy politicians had created an atmosphere of absence about everything happening there. Part of my task was to fill that void. It would take some time.

Eventually, I succeded in getting access, no small task. Amusingly, I employed a “power tactic” I learned in college while studying politics. A reminder that old lessons can stay relevant. I was told only two other “filmmakers” were granted permission to film regularly, not just once, and Speilberg was one of them. I don’t know if that’s true, but I’ll go with it.

Over the next year, up and through the 10th anniversary of the attacks and the museum's opening and beyond, I would spend hundreds of hours at the site. We produced over 80 weekly segments, an iPad book, and a two-hour documentary. We reported on the human and technological marvels unfolding at Ground Zero, from architects to steamfitters. I learned about high-pressure concrete and did shots of Johnny Walker. After work, of course.

In the photos above, you can see the site as it was. On the top left, I am standing in what would become the South Tower’s memorial pool. In another, bicycles. I lingered over the bicycles. We visited them and other artifacts or evidence from the attacks stored in Hanger 17, at JFK airport. This was their home until the museum opened. They were still locked to a bike rack years after their owners secured them and went on with what most thought would be a day like any other.

In my first and subsequent meetings with the museum and memorial staff, I was struck by the passion and purpose with which they advanced their work. No one needed to tell them it mattered. As a matter of fact, I didn’t meet anyone, and I met hundreds who worked at the site who didn’t ascribe higher meaning to the time they spent there. Many knew people who had been killed; others had served and left the military. Meeting an electrician who had done tours in Afghanistan at the site of the attack that made his service needed is quite a full-circle experience.

Much of what went on and into the site's rebuilding was fraught with politics. The WTC is governed by The Port Authority, which is beholden to the states of New York and New Jersey. States that were, in turn, governed by politicians from opposing parties. The site itself sits in New York City, and Mayor Bloomberg, an independent, was, as you can imagine, heavily invested in the process. I think I have all that right. It was quite a stew of politically and emotionally motivated interests at one of America’s most hallowed sites.

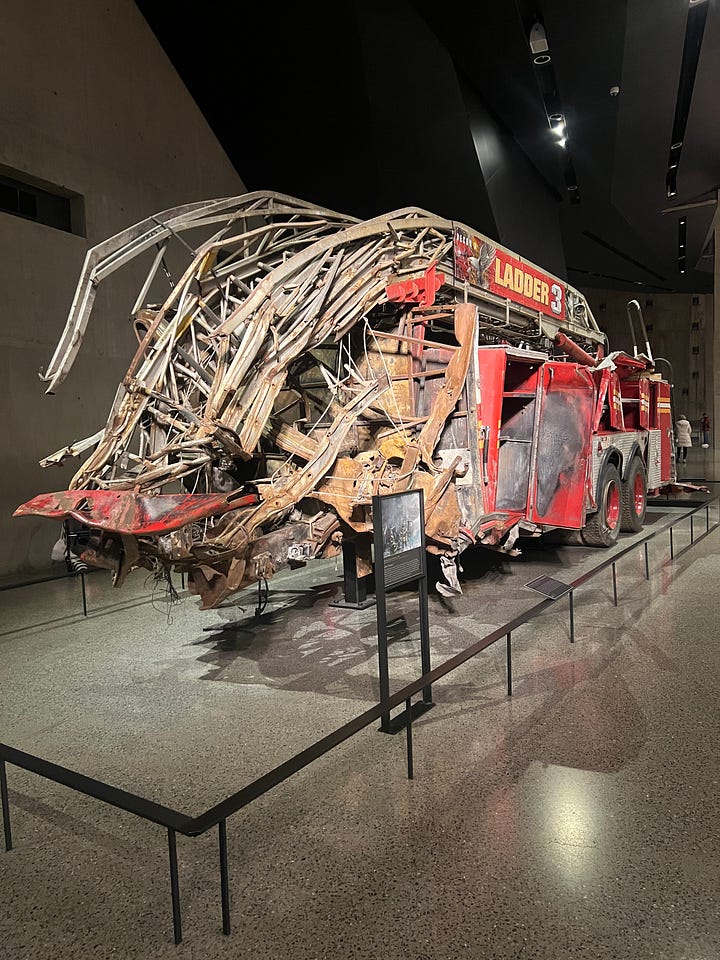

That did not deter the work of those tasked with memorializing the day for future generations. The aim was a museum experience that brings the day to life in all its searing pain and tragedy. So that it would never be forgotten, they endeavored to document the day as it happened, suddenly and painfully ending the world we all knew.

I was in New York that day and those that followed. It is and was my home. One of my younger brothers went missing after heading to the site to cover it as a photojournalist. Hours later, he surfaced with an experience that is hard to believe. He was very close to both towers when they collapsed. Just how close you can see below.

The days that followed are a blur. The absence of wounded. The smell. The sense of being powerless. The anger. All of it balanced against a city whose population seemed to get it. It united my home in a way we should seek to recreate without the motivation of tragedy. It was so painful. But for all this connection to that day and the work there, I had never been to the 9/11 Museum.

Then, on a sunny Thursday afternoon in January, I just went. I’d been thinking about it for a few weeks, years. But I always seemed to find a way not to go. Then I decided it couldn’t wait until tomorrow.

It was everything I feared. A painful, excruciating reminder of what the day and those that followed felt like. The museum was as described to me so many years before. A journey from the day before to the day off to the day after.

In an alcove, you could step away from the main path to see the images of people trapped and falling from the towers. It’s a dignified space where photography is not permitted. It is there and yet concealed from young eyes, too immature for such realities.

Artifacts and ideas I remembered from over a decade earlier were on display. ID badges, glasses; the mundane artifacts of our existence. I found myself rushing on a few occasions. I thought my subconscious must be pushing me along to save me the pain. I stopped and sat. I circled back to see it again. I finally saw footage on display that I’d helped secure for an exhibit.

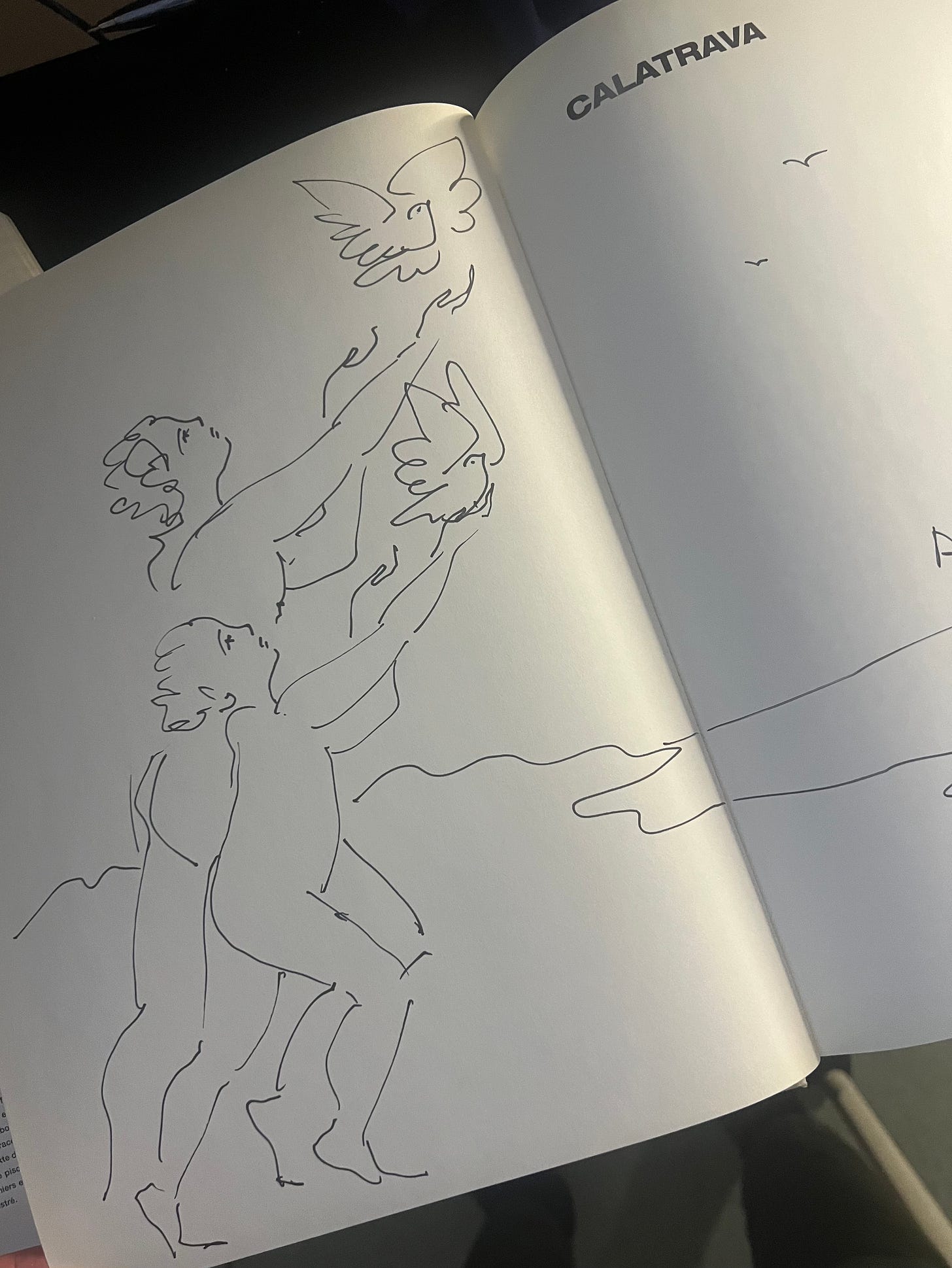

As I left I stepped out into the light I came upon the World Trade Center Transit Hub. Designed by Santiago Calatrava, it is quite a sight. When he and I met, he told me it would represent rebirth and that the design mimics birds taking flight from a child’s hand. He reached for a coffee table book of his other work and, in a flash, drew a sketch of my children releasing doves.

It was fitting to be reminded of this. That the future will come. That hope is up to you to have. That in big ways and small ways, we can rebuild. Don’t wait until tomorrow; it will never come.