I read it and thought, “crap.” The feeling has stuck with me.

It was a piece in the New York Times late last year.

The line that has stayed with me reads, “We are now almost a quarter of the way through what looks likely to go down in history as the least innovative, least transformative, least pioneering century for culture since the invention of the printing press.”

The printing press is over 500 years old.

Giving it thought. It does seem true. That the first 25 years of the 21st century have witnessed an unprecedented decline in creative boldness. We get a relentless cycle of remakes, sequels, and formulaic productions. Who dares count the police procedurals that fill television lineups?

This period may well be remembered as one of the least creative in human history, characterized by a pervasive fear of risk and a stifling profit-driven mindset. In the current cultural landscape, originality has taken a backseat to financial security—or the desire for it, despite the danger of regurgitation.

Movies are remade with alarming frequency. They are often stripped of the nuances and vitality that made the originals compelling. Sequels proliferate, each installment squeezing the life out of once-fresh ideas and beloved characters. Ultimately, they are often reduced to vehicles for revenue generation reliant on loyal fans or fanatics.

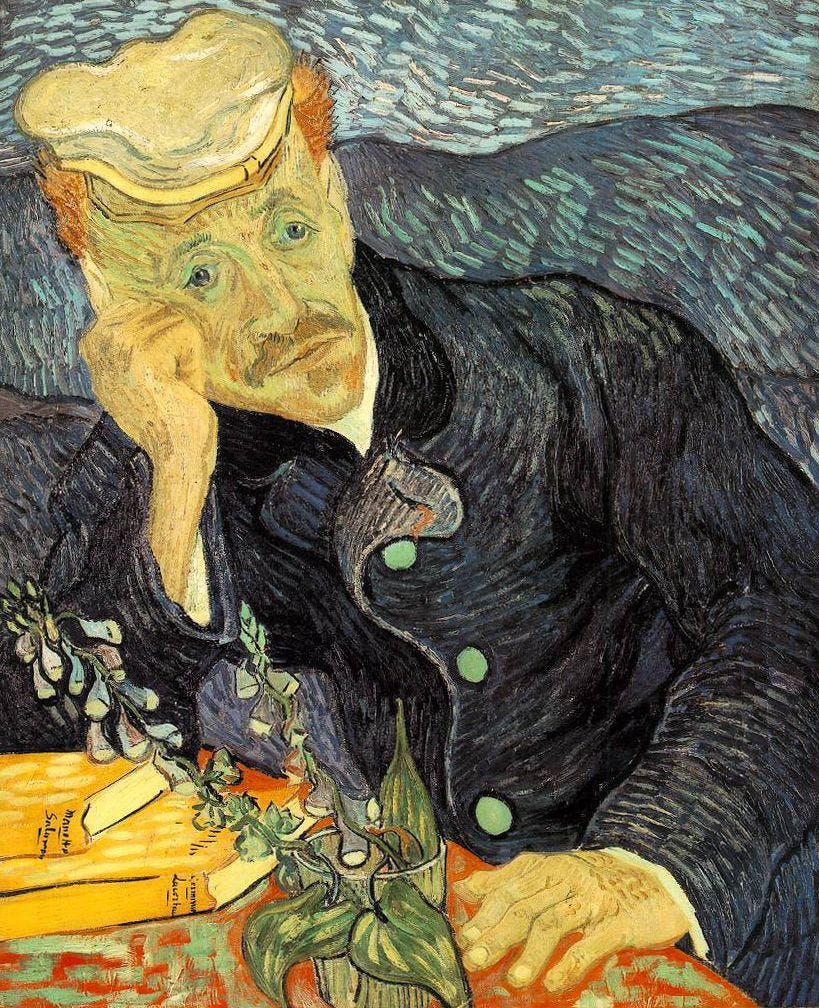

The stories of Vincent van Gogh, Emily Dickinson, Franz Kafka, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry David Thoreau, John Keats, and Oscar Wilde illustrate the quintessential struggle for artistic integrity. These artists, largely unrecognized and unappreciated in their lifetimes, dared to defy the conventions of their eras. Their posthumous popularity underscores a critical truth: genuine art and creation often require boldness and apparent failure. It demands a madness of will to challenge the status quo.

Vincent van Gogh, for instance, sold only a handful of paintings during his lifetime and relied heavily on financial support from his brother. Today, his works fetch astronomical prices. "Portrait of Dr. Gachet" sold for $82.5 million in 1990. Imagine that with inflation.

Similarly, Emily Dickinson published only a few poems during her life—one letter and ten poems, to be precise. Only after her death were her nearly 1,800 poems discovered and celebrated.

Part of this is distressing to me personally; I’ve been creating things during this creative doldrum. To be sure, no one is going to discover my poems or paintings and make a mint. But even my quantum of creativity has allowed me to learn about the process. It is fraught with fear, doubt, and angst. Sometimes, self-loathing at an effort that is not good enough. Alone in the process, you never quite feel right about a color or edit. In a collaborative environment, you can debate and argue over a word or image. Tensions rise, and voices can follow. In a modern workplace, this can be a problem. Human Resources are not inclined to encourage tension.

I’ve, at times, referred to this process as the “Creative Vise.” The nascent idea is placed in the tool, and an individual or group's ideas, whims, and approach apply pressure. The pressure builds, and if all is well, the end is something creative born of the same pressure that might result in a diamond. An analogy that overstates my work in brilliant fashion.

Too often, and not without good reason, in a for-profit creative environment, pursuing art for its own sake often takes a backseat. Risk and creative endeavor are stifled, with studios and publishers preferring to bank on the tried and tested. This reliance on data about past successes to guide future projects means originality is sacrificed on the altar of hoped profitability.

Franz Kafka's narrative style now stands as a pillar of modernist literature. It was largely ignored during his lifetime. He instructed his friend Max Brod to destroy his unpublished manuscripts upon his death, a wish Brod ignored. Kafka's works, including "The Trial" and "The Metamorphosis," were posthumously published and have since become literary cornerstones.

I often wonder how much beauty wasn’t saved by the likes of people like Max Brod.

The reliance on established formulas, data, and analytics, and the incessant recycling of ideas, can be likened to creative cannibalism. This approach gradually diminishes the essence of the original works, leaving behind mere husks of what once captivated audiences. Edgar Allan Poe, who struggled with poverty and personal tragedies, created stories that were initially undervalued. Only time, the fuel for most wisdom, has revealed their value. His influence extends across multiple genres, from detective stories to horror. It showcases the enduring power of original, daring storytelling.

The stories of Henry David Thoreau, John Keats, and Oscar Wilde further illustrate the transformative power of bold, risk-taking art. Thoreau's "Walden," has become a cornerstone of American literature and philosophy. It did not start that way. Keats' poetry was criticized during his short life. It is now celebrated. Wilde was ostracized and impoverished following his imprisonment. His legacy is one of wit and literary brilliance. The modern entertainment industry could learn much from these figures.

“Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth.”

― Henry David Thoreau, Walden.

Art and creation thrive on risk and the willingness to explore uncharted territories. This is when magnificence is created, leading to new and stunning works that captivate and inspire audiences.

Artificial Intelligence’s impact on the creative process further complicates this landscape. In my prior piece, "Artificial Intelligence And The Corruption of Power," I discussed the inherent dangers of AI in the hands of "bad actors." The true peril lies not in the technology itself but in us—the creators and manipulators of this power. As AI systems derive their knowledge from the vast expanse of human-generated data, our ideas, and creations, they inherit the biases and corruptions inherent in our society. All they can do is redo. This, in turn, exacerbates creative stagnation by favoring repetition. Regurgitation. Formulaic outputs. Be damned the daring, innovative ideas.

The dramatic expansion of AI and its potential to change life as we know it brings both hope and fear. The essence of art—its ability to surprise, challenge, and transform—may be lost in the pursuit of commercially viable, data-driven decisions. To avoid this outcome, we must recognize that true creativity thrives on human imperfection, risk-taking, and the willingness to embrace the unknown. The ability to take one more step. Face one more sunrise. Even when it seems no hope is present. The future has plans you can’t possibly know. Take one more step.

The creative industries must embrace risk and prioritize artistic integrity over short-term profits—but not value or long-term profit. Investment in writers, painters, filmmakers, and storytellers of every medium is akin to watering a seemingly barren field. Unknown to the uninformed, the seeds of great bounty lie hidden but ready to take root and become creation. To be sure, like any field, not every seed will grow. But well-organized and well-managed, the majority will.

With the “Creative Vice” in mind, it's important to remember that struggling artist may, in fact, be motivated by their hunger, their starvation. I can attest to the motivating reality of a deadline. Pressure can force good ideas forward from wherever it is in our minds that ideas begin.

Art, for art's sake, may be a high-risk endeavor, but it is the only path to creating works of enduring magnificence. Only by fostering an environment where risk and creativity are valued above all else can we hope to create new and stunning works that captivate and inspire future generations. These will, in turn, fill theaters, be read by millions, and be listened to by the masses. If the time spent consuming this art is deemed worthwhile to the audience, they will pay.

“Hope is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul And sings the tune without the words And never stops at all.” ― From "Hope" by Emily Dickinson

This is no small effort. The workings, at times machinations, of the media have created great fortunes. Behemoth companies are hard to turn or change. Altering course is fraught with peril. But the state of the business today is in flux and perfect for an adaptation in attitude.

Where will the future profits come from? Simply put, they come from human attention, our greatest commodity. Maintaining the world’s gaze and escaping this cultural rut requires risk. Leaders need to carve out spaces and environments where ideas can be pursued. Ideas that others consider crazy—a DARPA for the creatives. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is responsible for inventions like GPS. But success is rare. One head of the department claimed that 85% to 90% of its projects fail.

When Stan Lee first pitched Spider-Man, he was told by his publisher that it was the “worst idea I have ever heard.” This was not, in fact, the case. Lee once said of this experience, “If you have an idea that you genuinely think is good, don’t let some idiot talk you out of it.”

My cursory math shows the Spider-Man films grossing over $3 billion. This is a reminder to chase the crazy idea.

I believe that the task is not complex, perhaps hard and demanding. Like digging a ditch. Persistence is key. A form of courage is demanded. But it is not rocket science. Be sure there are a great many wonderful ideas hidden by the noise of franchises and sequels. Films, plays, books, and music exist beneath our current, seemingly featureless cultural plain. Some get found, and others have champions. If the powers that be don't alter course and take us out of this “least innovative” period, they will fade and be replaced. Empires do crumble. Dynasties die. The unknown will be found. Discovered.

So, if you seek to create, don’t doubt yourself. Don’t be discouraged. Some of the best were filled with grief for their apparent failure. Their lacking. Find yourself a Max Brod, or be one yourself.