It is not easy to get half, or more than half, of Americans to agree on something. So, when I read that most Americans support building a wall along the US-Mexico border, I paid attention and considered what works. According to the poll, 53% of Americans now approve of a border wall. That’s an almost 10 percent increase from the 44% of support it received during the Trump presidency.

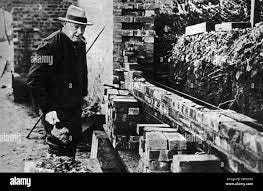

Walls have many purposes, but security, safety, and protection are primary among them. Winston Churchill famously built the brick wall around the kitchen garden at his country home, Chartwell. A kitchen garden is a space just outside a home dedicated to growing food. The wall protects these valuable items from animals that might eat them, such as deer and rabbits. The wall also protects edibles from the elements; it provides a sort of microclimate.

Winston once said, “…200 bricks and 2000 words a day…” His routine was such. When I visited Chartwell to chronicle the life of the man who led Britain during World War Two and made it clear to others that Hitler could be stopped, I found myself thinking a lot about walls and what they are good for.

Churchill’s kitchen garden wall has a clear and basic purpose. But it is also an admission of inability. It represents the inability to stop what might damage your crop from damaging your crop. It symbolizes the limits, his limits, to forestall the danger his cabbage and carrots faced. A harsher or more hyperbolic way to see Winston's wall? As a sign of his weakness. He could not protect his produce without it.

In an era when the construction of physical barriers between nations has become a symbol of security and sovereignty, this leads me to ask, “Do strong nations build walls, or do they go where the danger lies and deal with it there?”

Before we continue, a point of certainty: Sovereignty and security in a global reality are as important as the free, useful movement of people, their ideas, and the fruits of their labor. Knowing who is in your country is akin to knowing who is in your home. Likewise, walls, moats, fences, and fortresses have roles in a complex world. The question I ponder concerns something more than this basic need. I wonder if, like many things, we haven’t mythicized the capabilities of a wall to solve a complex problem.

As I think about it, my mind wanders further from the real. I’m reminded of the poem "Mending Wall" by Robert Frost. It offers a poignant reflection on the impact of divides.

Frost's exploration of the spaces between us revolves around an annual ritual between neighbors in which they rebuild a stone fence that divides their property. As I read it, Frost is the neighbor questioning the need to have the fence at all, eliciting his neighbor's reasoning and the phrase for which the poem may be best known;

Good fences make good neighbors.

However, all quotes are out of context; it is important to know that the poem, on balance, reveals a complex truth: barriers may offer the illusion of safety, but they fail to confront the reason the wall is needed. Just a few lines later, Frost asks;

Why do they make good neighbors?

In the modern era, I wonder how any wall or barrier can address what drives individuals toward migration. Will a wall stop people from fleeing violence and poverty as they pursue a more hopeful existence?

In looking into this idea, I read in Foreign Policy, “All told, the countries subject to some form of U.S. sanctions collectively account for a little more than one-fifth of global GDP.” That’s a lot of people who don’t dictate policy, who may well agree with the idea of the sanctions and are powerless to change their country and the reason for this punishment. This punishment and subsequent pain cascades down from those in suits and power. It is not an unfamiliar dynamic; the meek and downtrodden suffer at the feet of power.

Frost’s poem challenges the notion that walls and barriers can effectively protect us from our fears. Instead, he suggests, they only deepen the divisions among people. By obscuring the shared desires that unite us all, we grow further apart and suspicious, which often leads to escalation."Mending Wall" is a testament to the idea that true security lies not in erecting walls but in addressing the underlying issues fueling conflict and displacement.

All this prompts a broader discourse on how we, as a global community, can navigate the challenges of the 21st century. And no matter what your politics, we are a global community, if only because of what “inter” in intercontinental missile means. Real dangers exist. Be sure there will be times when violence of action and warfare are demanded. However, the solutions to our most daunting problems lie, almost universally, in the pursuit of understanding and cooperation across the divides that separate us. I’m not naive about the difficulty this course presents. Powerful nations seek to exert their power and remain able to do so. My point is that walls are a barrier to this more than an aid.

This brings us to the crux of the matter: walls may offer protection but do not solve the underlying problems that necessitate their construction. Never mind that the act of construction takes time, and with time, the issues and problems will change. The Maginot Line was a series of barriers, forts, and defenses that stretched along the border of France prior to World War Two. A reaction to fears of German invasion after World War One. In this case, the defenses were designed for the last war, not the next. The wall is reactive, not proactive.

The Maginot Line was indeed a formidable defense. I’ve met a few historians who made variations on the joke that it was a great fence but lacked a gate from which those it protected could exit and fight. This isn’t entirely fair. It did provide value, but ultimately, it did not prevent defeat at the hands of the Germans at the beginning of World War Two. This wall alone did not provide a safe haven.

A wall might stop rabbits from eating your carrots or make a boundary clear and keep roaming kids off your lawn, but free will, human migration driven by the desire for a better life, hasn’t been stopped by anything for long. People will find a way to provide for themselves and their families. Similarly, those seeking conquest will find a plan they believe is capable of victory. Motivated, all will face great danger to do so and have for as long as history records. Or, as is quite clear, they will die trying.

True security comes from proactive engagement with these issues. Addressing the root causes of migration, such as economic disparity, violence, and political instability, requires a collaborative, international approach that goes beyond erecting barriers.

In a simpler context, consider a personal moment—an issue in your life that demands a difficult conversation. At times, we procrastinate and delay confronting the issues that concern us. We wall ourselves off from the matter. But invariably, after a hard talk, we are left with more regret over the delay than lament about the conversation itself. The delay is a defensive act. The talk is proactive, engagement, and even if imperfect, it is progress.

Again, none of this is meant to suggest that sovereignty and strength are a bad idea. Knowing who is in your nation is vital. Knowing who is entering your nation is vital. Invasions do happen, and invasions come in waves and drips. There are dangers in the world that can’t be ignored or turned over to diplomacy alone. You may recall Theodore Roosevelt’s famous line, which he first wrote this way in a letter, “I have always been fond of the West African proverb: ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.’” The strength to strike, force, is needed.

To lean on literature again, we turn back to Robert Frost, who wrote in "Mending Wall,”

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

Frost’s poem, published 110 years ago in 1914, ends with what might be the most insightful, probing, and honest element. After all the back and forth, all the discussion and debate, the neighbor returns to his refrain, unaltered and unmoved in opinion. The poem reads,

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

I estimate that, like many “solutions” leaders suggest, a wall is a cosmetic solution to a structural problem or a global problem. If you prefer something more blunt, you can go with “lipstick on a pig” or “polishing a turd.” But if you say it enough, it is a “crisis,” an “invasion,” a wall will stop it, then something amazing happens. People begin to believe. Say it enough, and you can make it true, and people will agree. This can leave us stuck in our ways, chasing solutions that only wall us in and limit how far we can go.