I didn’t understand a word. They weren’t speaking English.

But I understood.

The video clip is barely a minute long and it shows a Ukrainian soldier face down in the dirt. Gunfire and explosions are heard nearby. Another soldier leans over him and they speak. It is clear the man on the ground has found a limit, his limit. The pain in his voice. The urgency with which his comrade speaks to him. You understand. They are in danger.

You can watch the whole clip here on funker530. One of the comments left on the video offers a translation from Ukranian. The soldier on the ground is asked, “What happened, brother?” Then he is assured, “Everything is ok…don’t be afraid.”

Everything is not “ok.” Fear is wise. Still, as gunshots ring out, he rises. They join other soldiers maneuvering along the edge of a field.

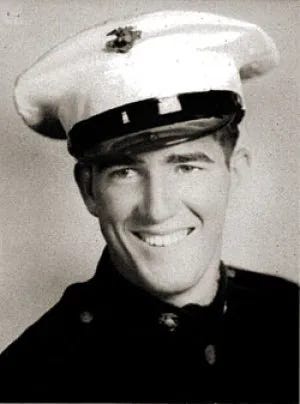

Witnessing the terror reminded me of all the work and time I’ve spent with combat veterans. My mind’s eye saw Don McCullin's famous photograph of a US Marine, frozen by what he had experienced during the Battle of Hue in 1968.

Among many things about this photograph that have stuck with me is that McCullin can’t find a difference between the five photos he took of this man. In an interview, the photographer once said, “I kind of dropped down on my knees and took 5 frames with my 35mm camera of this soldier and he never blinked an eye, his eyes were completely fixed on one place. He was staring off into the horizon and every negative I took of this man is identical I checked them all out thoroughly.”

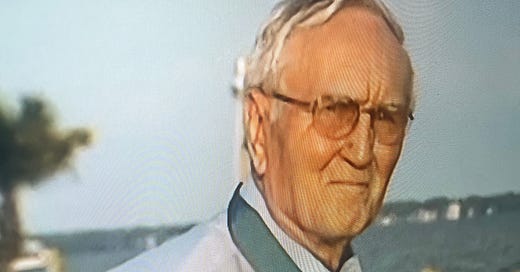

I know a number of veterans who have encountered this suffering. Some experienced it themselves. They were pushed beyond their capacity. Others simply suffered and witnessed the pain of their friends. One was Colonel George Day. A man I knew as “Bud.”

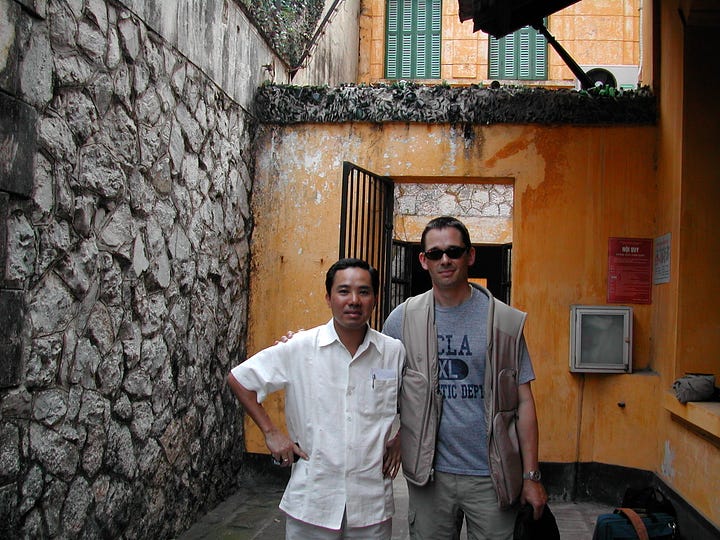

We met years ago. I interviewed him about being a pilot in Vietnam. About being shot down. About hiding in the jungle. About being a prisoner of war. We talked about being tortured. After the interview, we stood in his backyard looking out over the water.

Bud said it with confidence. “Everybody breaks, Martin. Everybody.” He went on to add that if they’ve tried, done their best to resist, and fought with all their might, you can’t hold it against them. “Everybody breaks.” His admonition about the fact we all have our limits has pervaded my approach to life since that day.

Colonel Day’s authority on the matter of resistance came to him while he was a prisoner of war in Vietnam. He was held for five years and seven months. After being shot down in 1967 he was quickly captured. On his first day in captivity, he was hung from his feet, for the day.

He managed to escape on his fifth day. He was barefoot. In nothing more than what amounted to underwear. I remember Day telling me, “I was essentially naked.” He made his way closer to friendly territory. For two weeks, without food or water, he succeeded in evading the enemy. Then, just a mile from a major US base, he was captured, again.

“I walked into an ambush,” Day told me. Amusingly, at least decades later and safe at home, he recalled they were looking for troops coming from the other direction. He walked in the backdoor.

Eventually, he was taken to the notorious prison camp in North Vietnam called the Hanoi Hilton. He was routinely tortured. Torture was common.

Prison guards bound arms and legs with ropes and then dislocated them. Food and medical care were inadequate. The physical punishment was compounded by isolation and solitary confinement. One prisoner held there was captured six months after the Beatles first toured America in 1964. He was released in 1973, three years after the famous band broke up. The harsh reality pushed men to, and beyond, their limits. Some cooperated or collaborated. Others died.

Bud Day came home in 1973. When he died in 2013 one article on his life carried the headline, “Bud Day, 88; as Vietnam POW was tortured, kept secrets.” Shot, bones broken, beaten, starved, he kept his secrets. But when we met years later he made a point of telling me we can’t hold it against those who resisted and were broken. They did not give up or give in, an external force broke them.

In my life, professionally and personally; Leading teams, helping friends even seeing strangers struggle I often think about how much people have left in them. How close to breaking are they? It’s an odd way to put it, but I try to think about what I don’t know. What burden, fear, or pain do they carry that would leave me less, unable, broken? How would I fare if I had walked in their shoes?

I generally believe people try their best. But sometimes that isn’t good enough. Perhaps they don’t know any better. Perhaps they haven’t been trained. Perhaps they are burdened by a trauma I am unaware of. I’ve been told this is empathy. But I’m not sure. That seems generous. At work, it is a way to manage assignments and expectations. Being mindful of the fact we all carry things that haunt us. Haunt might be a bit hyperbolic. But it makes a point. As a leader, you need to remember what people are dealing with, even if you don’t know.

In daily life, I try to default to this mindset of understanding when someone is driving like a fool. Perhaps it’s an emergency. The streets of NYC are now, as always, home to people with burdens and baggage that would break most of us. I have no idea what they endured to get to this point in life.

Another veteran, Giles G. McCoy taught me about that external force. He was a doctor when we met. But I was interested in the four or so days he spent floating in the vast Pacific Ocean. He was a Marine on the USS Indianapolis. That ill-fated ship was sunk toward the end of World War Two. Sunk after delivering the atomic bomb. The rescue was delayed. Gil watched and tried to help as the elements broke man after man. First sharks. But then the horror of being abandoned set in. He told me of men slipping from their life jackets and simply vanishing below the surface. They had had enough. Others, delirious from dehydration and malnutrition, began to see things. They swam to islands that were not there. They saw mirages below them that offered hope. They dove down to investigate. They never resurfaced.

Gil went into medicine after the war. As he told me, he was inspired in large part by this ship’s doctor. A man he witnessed continue to render any aid he could to shipmates. Perhaps you have seen the movie Jaws. The character Quint, played by Robert Shaw, was on the Indianapolis, like Gil. One of his famous lines is, “I'll never put on a life jacket again. So, eleven hundred men went into the water, three hundred sixteen men come out, and the sharks took the rest.” The truth is, sharks didn’t take the rest, the rest were broken by nature.

Art and reality often lean into this dynamic, a protagonist needs a challenge. I remember rewatching Saving Private Ryan and thinking of Bud Day as Corporal Timothy Upham, played by Jeremy Davies, cowers on the stairs at the film’s dramatic conclusion. His comrade is close by fighting for his life. Upham does nothing. Eventually, as Upham sits by, his fellow soldier is killed by a German. It is an excruciating scene.

A quick search will find no shortage of people who call Upham a coward. But with Bud Day’s “everyone breaks” wisdom in my head I reconsidered.

The first time we see Upham he brags about his German language skills. “Clean has a touch of Bavarian,” he tells the character played by Tom Hanks. He has not seen combat. He hasn’t fired his weapon since basic training. He attempts to take a typewriter with him. As he puts it his job is to, “make maps and translate.”

Upham joins the mission to save Private Ryan. He rises to the moment. Until he hits his limit. Untrained for combat he breaks. After his fellow soldier is killed he lingers on the stairs until another American comes and grabs him. It is much like the footage of the Ukranian soldier. Two men, one real and one fictional, are broken by combat. Then help arrives.

As the film continues, Upham hides as Germans rush by and kill other Americans. Then he sees the Tom Hanks character shot, mortally wounded, by the same German he sat by and let kill his friend. Suddenly, an airstrike routs the Germans and Upham rises from his hiding place. He raises his weapon and halts a group of retreating Germans. After a moment he shoots and kills the man he let kill his friend. In ugly and grotesque fashion, a stance success in warfare demands, Upham returns to the fight.

In the clip from Ukraine, a real young man is pulled up from his low, his misery, and rejoins the fight. He heads off down the edge of the field. Then moments after being incapable of anything another soldier stumbles and drops to a knee before him. Without hesitation, he slows and grabs the man’s backpack, helping him up. He holds on as the man regains his balance. This is that cascading reality of being there when people need you most. We are able to help when we feel we will be helped.

We live through peaks and valleys and plateaus in our lives. We can all break. But we can all be unbroken. We achieve nothing of significance alone.

Author’s Note: Over the course of my journalism and television career I’ve traveled the world to document the actions of individuals during warfare. I’ve met and interviewed in some capacity 100s of veterans, the actual number might be in the 1000s. This is an ongoing series to memorialize my experience and further record remarkable acts and attitudes the worst of humanity can inspire.