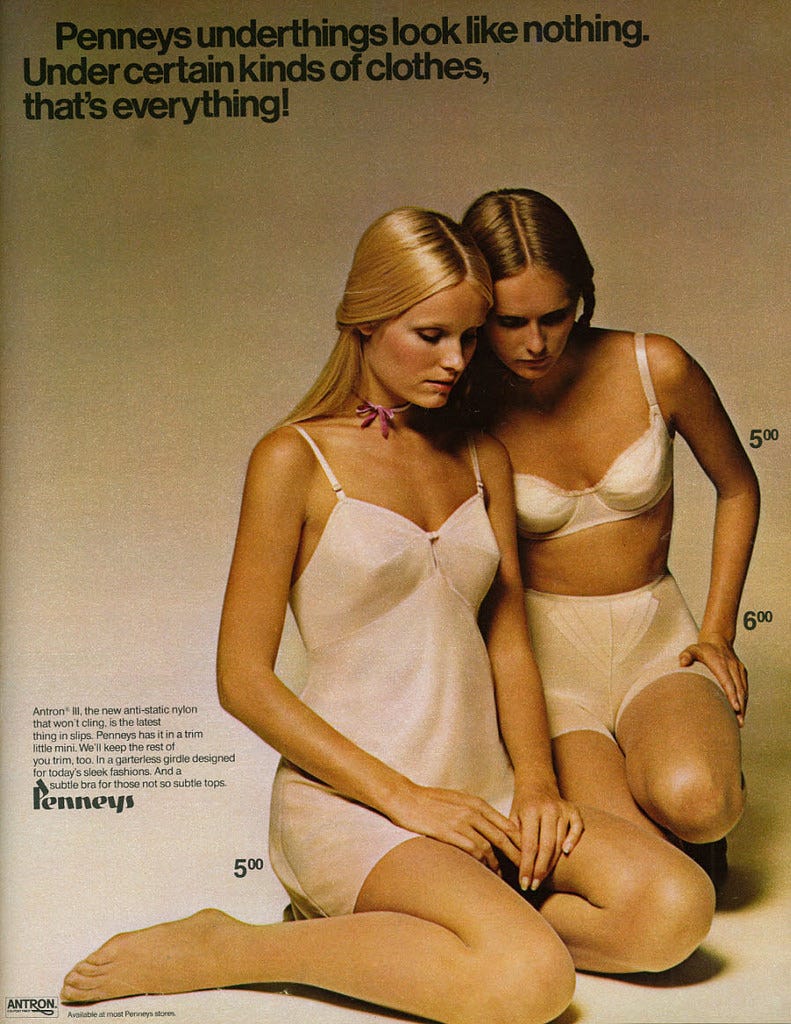

The models just stripped. Right down to their underwear. Casual. Calm. One lit a cigarette. It’s the first time I remember realizing how much happens that we don’t see. Just how many people it takes to do the simplest things.

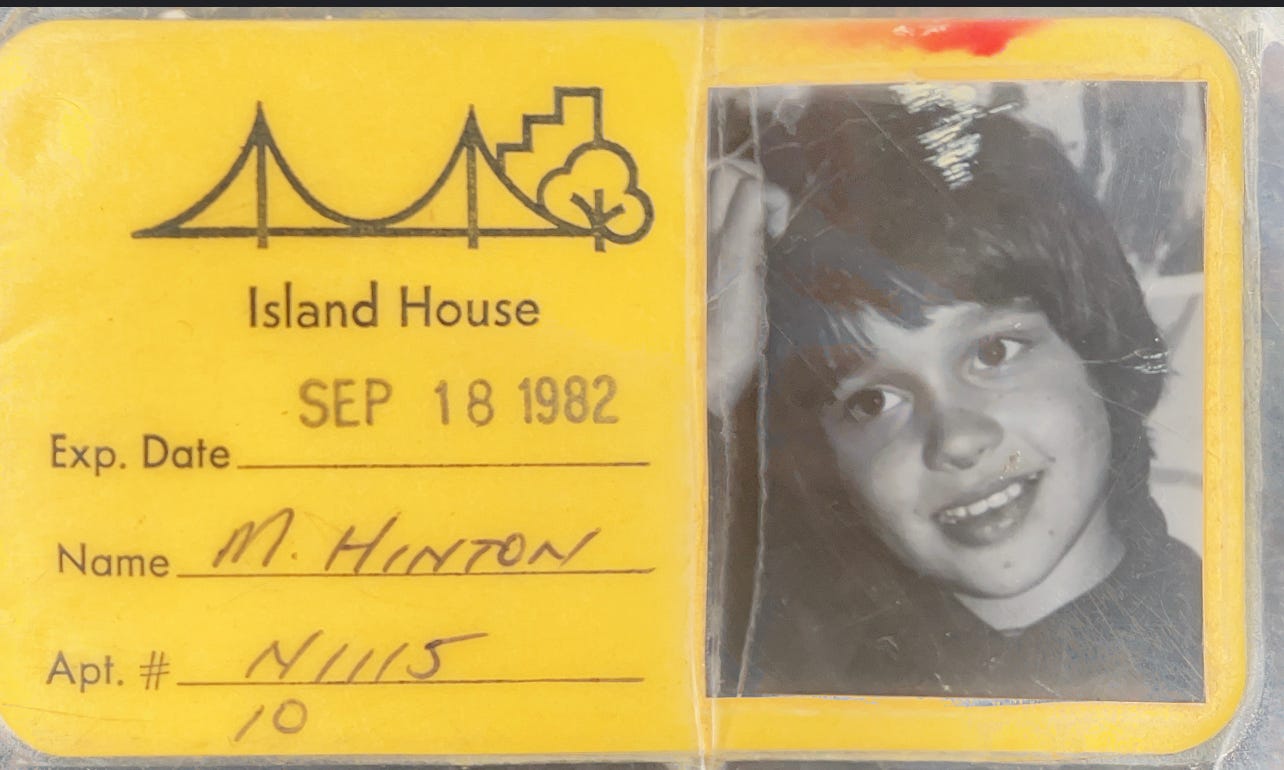

Rewind to New York City in the late 1970s. Specifically, Roosevelt Island. It sits in the East River off Manhattan. I was about 9 and only a few years removed from life in London, England. I had a toy gun. I had been playing war with some friends and was on my way home. Back then the island was far less developed. Vacant lots and abandoned buildings made for some pretty good playgrounds. My trip home was a meandering journey. A path only the clean slate of a child’s mind can navigate.

What stopped me was a fashion shoot. The cadre of models, a photographer, and a few others dealing with lights and reflectors must have intrigued me. At one point my spectating was noticed and several of the models and crew chatted with me. They had determined I was clearly their security, keeping a watchful eye over them. I probably liked that and lingered longer. So long that when they stopped to change they invited me into their RV. I was a child and after a moment of thinking, “Are they kidnappers?” I went in.

Inside their motorhome, the models undressed. “Wardrobe change,” someone had announced. But they were in no rush. They laughed and joked in their underwear. All the glamour and pretense of high fashion were literally and figuratively stripped away. They offered me a Diet Pepsi. “Is it poisoned?”, I remember thinking. It was dreadful. Worse than poison. I sipped it politely. Haven’t touched it since.

Recently, I found myself thinking about this moment in my life. I’d gotten a glimpse of all that happens. All that isn’t in the finished product. My mind considered what I knew about collaboration and how big things come to be. I also wondered how common this knowledge is.

“The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Aristotle

I’ve worked in television and journalism for three decades. In television, news, and non-fiction specifically, most consumers see the host or reporter and not many others responsible for the work. The anchor of a TV show, ideally, holds the viewer in place. Lost in that perspective is the truth. A truth just beyond the camera’s frame.

I was in Indianapolis one of the first times this absence of knowledge hit me squarely in the face. Oliver North and I were there for a few things, including a book signing. At one point, after getting his book signed, a fan asked Ollie how he did it all. The lovely man said something like, “How do you find the time to write all the books, do the research, do all the interviews, write the scripts, do the radio show?” Ollie smiled, gave me a sideways glance, and said, “You should meet Martin. He can explain.”

Truth be told it’s a compliment. Well, I took it that way. I am not a public figure. The job is to elevate the host and make them the person each viewer seeks a connection with. Beyond that, the best TV floats off the screen. The audience simply sits back and it reaches them. Watching is effortless. One of the finest compliments I’ve been paid relates to this. On this occasion, I’d produced a very long segment, roughly 16 minutes. After watching it air on her show an anchor came up to me and said, “That was amazing, and long, what was it like 8 minutes?” To have taken 16 minutes and left someone unaware of it is a bit like casting a spell. I think this illusion suggests to viewers, subconsciously, that the content they are watching took little effort. It was easy to watch, it must have been easy to do. Nothing could be further from the truth.

News, in particular, is extraordinarily difficult to do well. When you begin to manage people it takes on a complexity fraught with unexpected events. New news is always there. Organizing a team's efforts, and guiding them, while relying on them to advance a project based on their own instincts and knowledge can be painful. They need independence. You need to sit back, at times, and let them do their work. Be wary of the boss who rewrites everything making it all the same. I have joked it can feel like herding sheep. At times it can look like a mess. Sheep everywhere and nowhere they should be. But ebb and flow shouldn’t alarm. Well shepherded, the parts find their path. Then it all seems to work and the flock moves efficiently through a gate to a new pasture or, in this case, production.

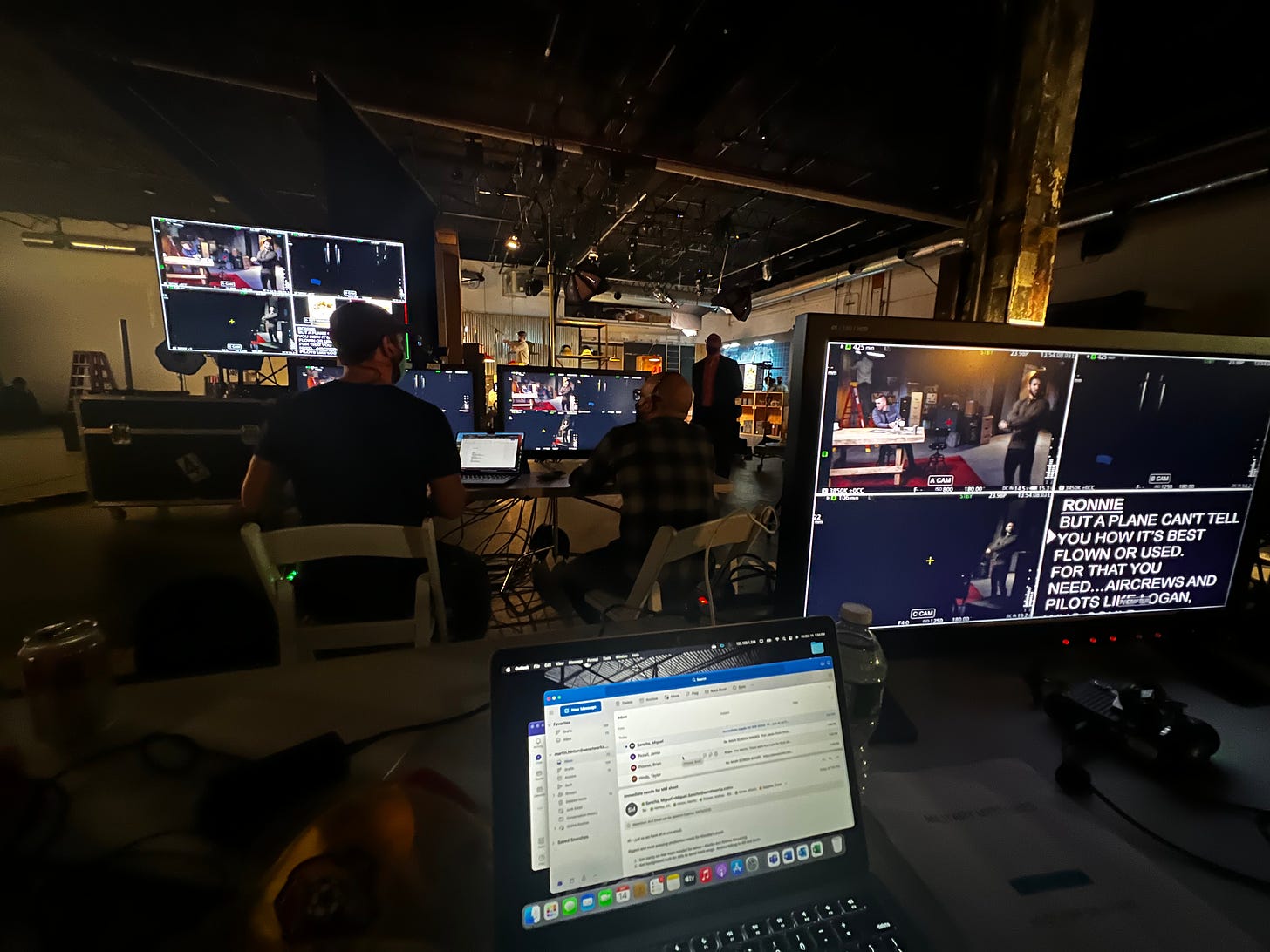

Last year I was an Executive Producer on a new TV show that will air later this year on The History Channel. It’s called The Proof is Out There: Military Mysteries. This was an eye-opening professional experience. Before this, I’d spent 22 years at the same company, the same corporation. In an actual office. This new job was all freelance, all remote, production of an entirely new show.

It was lovely, well almost all lovely. Plenty of it wasn’t that great, but challenging tasks come with hardship. Over the course of eight months, the format changed several times. The show’s name changed more times than I’d care to recall. None of it was unfamiliar. The creative-vise demands pressure. It all happened over Teams or Zoom or Facetime or text or email. Post Producers and Field Producers worked with Archival PAs and editors from wherever they happened to be.

At times the remote element was difficult and disorienting. But things progressed. We turned ideas into interviews or shoots. Those became transcripts and scripts. Those became rough cuts of segments. These became elements within the rough cuts of episodes.

We shot the wraps on a set in Brooklyn. It was in those tense, busy, six days that I remembered what this odd business does to me on a level I don’t control. It makes me feel something joyful, even when one of the many things that go wrong goes wronger.

Consider the photo above. A viewer will see just two of these people when the show airs. All these people, in different places, with different backgrounds, and different expertise come together to create something that is real. The audience will see hosts and experts, but beyond credits have little notion of the dozens of people, from executives to production assistants, who made their viewing possible. I love knowing about this wizardry behind the curtain. I left on the last day of filming and thought about how wonderful it is to be part of something like that.

I also thought about the first time I got behind the curtain and realized just how many people it takes to “make the magic.” As a nervous child sitting in a motorhome while underwear-clad models laughed and prepared. All the posing for the camera was set aside as they prepared for the next moment in the light. Make-up and hair were touched up. Conversations about the next set of outfits were had. Everyone with something to add.

Something to add. The need for collaboration certainly isn’t exclusive to businesses with cameras. Neither is the misguided perspective that an individual does all the work and is responsible for the end product. Perhaps that’s the magic of successful collaboration. It creates an illusion. It creates a whole greater than the sum of its parts. A product that can mystify. One that some reflexively attribute to individual genius. While individual effort is vital and essential, the truth about how it all gets done is far more complex and populace.