It all begins with Sebastian. Not a hero of old wars enshrined by a marble statue or etched in towering bronze, nor a name echoing through history books. Just Sebastian, 22 years old, a quiet name resting among others you never knew, on a stone in a Danish countryside graveyard. And me, leaving Dublin Airport to visit him, carried by some imperative I can't quite articulate, except to say it involves him.

Airports, terminal coffee even when good too expense, pastries unwrapped and forgotten. Dublin to Copenhagen, one flight blending in with countless others, seamless and simple yet layered with a thousand complexities. My mind drifts, wandering corridors of memories, how wars have shaped, us, me, professionally and personally. Military histories, wars past and present, the meticulousness of my fascination colliding with my revulsion. From grandfathers at sea, mostly evading torpedoes, and beneath The Blitz transfixed by Buzz Bombs, to new acquaintances in the countryside of Vietnam and retirement homes in the desert. Sebastian brings clarity amidst my scattered thoughts.

Here I am. On a day sandwiched between the 80th celebration of VE Day and America’s Memorial Day. Why him? Why Denmark?

Sebastian, part of that small, brave country which responded so swiftly when towers fell and our world, as we'd known it, shattered. Denmark: highest per-capita losses. If you're Danish, the chances are great that you've buried someone you loved. Someone you knew. The chances are greater than any other. Close your eyes and imagine Sebastian’s face.

The world moves past this rise to our aid far too swiftly, grasping at GDP NATO percentages, political calculations, the mathematics of burden-sharing. Too many with power and means seem willing or perhaps even eager to discard the value of those who make their perch possible. And lost in all this arithmetic are men like Sebastian, who volunteered, who went willingly, who believed.

I remember that day vividly, standing in New York City, my city. The towers crumbling, surreal against a flawless September sky, and the peculiar smell afterward, grotesquely bitter and sweet. A burning, acrid mixture lingering for weeks. A constant grim reminder. I recall the fear, the anger, the helplessness. The suffering. Seeing others, hours spent, desperate for news of family, of friends. My own brother survived by the slimmest of margins. The rawness of those moments never truly fades, etched deep into our collective psyche. Time heals, and then you are reminded. Then you are there again. Sebastian's journey to Afghanistan was a direct line from those events, connecting my home's pain to his sacrifice.

Stepping onto Copenhagen's streets for the first time feels oddly familiar. Impossibly calm and quiet. The sun is bright. The deceptive warmth of a northern city heats me. Soon I'm lost amid a language that wraps around me in friendly confusion. I wander to my first stop. The Citadel, an old fort. Within it is what draws me.

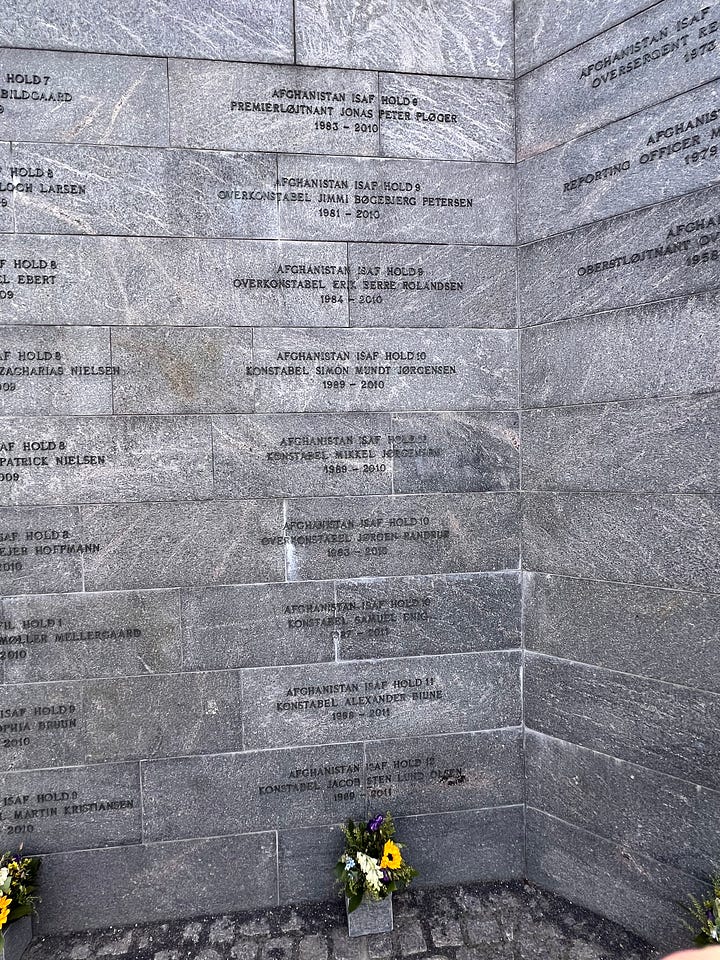

The memorial. Names upon names in tidy, relentless columns, clean and brutal in their simplicity: Martin, Johnny, Mark, Alexander, ages 21, 24, 26, all too young. And Sebastian, nestled amid them, silent and profound. Fifty-two lives in all. Lost far from home because of an act far from home. Because a friend asked for help. And they replied, "let's go." What were their lives like?

Wind rustles through unfamiliar trees, a subtle backdrop. The city's pulse continues around me, ignorant of my pilgrimage. I'm reminded of other memorials I've visited, minimal, stark, powerful. The Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC, every name exact and unyielding. Others less know. Billy Fiske's grave, an American Olympian buried quietly in England after he crossed an ocean to fight fascism before the country he loved rose to the challenge. Some people understand there are sometimes things larger than themselves. Sebastian, too, understood.

I read about him before coming. A wonderful article. Sebastian's parents speak of signs that comfort and puzzle them. His father, Niels, says, "Some signs appear that are hard to explain. And you become very aware of that when you lose someone you love so much." Rainbows and shooting stars above Sebastian's grave have become part of their lives, moments that feel significant and reassuring. Elena, his mother, dreams of him vividly, always waking happy, as if Sebastian's brief appearances keep him alive within her.

Later, after the memorial, laughter at my hotel, no, hostel. My first encounter. Why? The novelty. To say, "I have." In this case, a capsule, tiny and high-tech, embarrassingly novel to someone like me, decades removed from the typical guest. Alone in my small pod, claustrophobia pushed away by the gentle amusement of this situation, I reflect: Sebastian, somehow, has given me this moment. A small, unexpected joy in his quiet legacy. A silly moment. Perhaps we linger best in small anecdotes - quiet impacts rather than towering statues.

Night falls late, slow northern twilight drawing out conversations and casual gatherings. I sit outside with my Carlsberg, savoring a simple dinner amid the murmurs of locals and tourists. Tomorrow, I'll travel deeper into Denmark, towards Sebastian, but tonight, I merely exist in this gentle atmosphere. A marvelous collision of old and new because of Sebastian.

Morning arrives bright, clear, I slept well. Navigating Danish trains and buses is like revisiting younger days when maps were paper and words had to be translated through phrasebooks. A short coffee in a beautiful old station, an amusingly broken conversation with the server. There's a quiet bravery in being a stranger, in needing help and accepting it gracefully.

Outside the bus, the countryside unfolds, green and calm. I step off into uncertainty, consulting my map I travel 30 meters or so. Then a right turn. Down a path that enters some trees. A windmill fitting in my sight. Horses watch me pass, indifferent, majestic. Songbirds narrate my journey. The path ends and a right turn. A few hundred meters to go. A road lined by homes. Quiet. The church appears. I turn the handle on the gate and begin to search. It was brief. There behind the humble building, I find him. Sebastian's grave is modest, marked simply. Beautifully adorned by nature itself.

Sebastian, or "Seb" or "Sebber," as his family called him, was known for his voracious appetite for life. His mother recalls, "He lived life as if no one in the world could knock him down." Niels admired his son's unwavering positivity, once saying, "If everyone was like Sebastian, there would be no war in the world."

Laying flowers and a note, I sit nearby. Suddenly anxious. Is this intrusion? Presumptuous? Will Sebastian's family understand my gesture? Yet, having read enough, I trust they might see the sincerity. Silence envelops the scene, but for the church bell, the birds and distant children caught between laughter and dispute.

I contemplate Hemingway's harsh truth about war, no glory, no valor, only death and loss. Afghanistan and Iraq present the same. Why? Was it worth it? It is always the worst thing we do. Yet war persists, and we argue its morality endlessly. But, pacifist and warrior alike should realize, remembering those lost can support either argument. Their sacrifices underscore both the necessity of peace and the necessity of courage.

Sebastian gave me more than anticipated, a humorous hostel experience, a journey through landscapes I'd never imagined visiting, a moment of peaceful solitude and reflection at his grave. Perhaps this is how he would prefer to linger, not as a towering figure demanding awe, but quietly shaping subtle moments in lives he never knew.

I began by saying it all starts with Sebastian. But that's not entirely true. We seem to live in an age where "please" and "thank you" are a distant follower, too loud and ignorant. There are numerous examples of this. They come from all quarters. But the recent Signal chat escapade exposed the level of disrespect some in the heights of power hold. There are genuine debates to have. Important policies for serious people to settle on. But the use of the word "free-loaders" to describe European contributions to defense stuck with me. It reminded me of another phrase, "freedom isn't free." Who has paid a greater price than the dead? What load is borne by their loved ones? Their mothers. Their fathers.

Sebastian and his fellow Danes fought for something bigger than themselves; they left us enriched. In forgetting that we dishonor ourselves. In insulting them, we expose ourselves as unreliable.

In remembering them, we remember ourselves - our choices, our morality, our humanity. We remember the friends who stood by us. And in the end, perhaps that's enough. We just need to do it and act accordingly.

Some say we live in hopeless times. I do not agree. But I understand. If you need a reminder that the world is full of good things, maybe your next journey can include finding your own Sebastian. They are everywhere. Someone you never knew existed, yet whose life might quietly enrich your own. On the way you might have a laugh somewhere new. Get lost and meet a stranger who helps. Be carried by songbirds. Visiting your "Sebastian" might even give you hope, not in history, but in the fact that the world is full of good people.