A Gallup poll came out last year. It arrived with this deadline, “Americans' Trust In Media Remains Near Record Low.” I can think of a few reasons for this “low.” The one I sometimes fixate on is that some members of the public view members of the media, journalists, as arrogant. I can assure some of us are, just like any group of people. Another reason that recently came to mind is that people don’t know how stories get picked. This fuels distrust in why stories are chosen. Who does it benefit? Who is rewarded?

It’s a fair critique. The impact of a story appearing in the right place, or a high-profile place, can have a significant impact. It can change public policy, raise money, and in some cases, it can destroy lives. But this is about the opposite of destruction. Or, I hope it is.

This all crossed my mind last week. I was in a meeting and presented with this question. “How do you pick the stories you do?” It happens in a variety of ways. Sometimes it’s obvious, a tornado or other natural disaster. You also get tips. Then a good journalist observes and asks the question, “What’s up with that?” This inquiry about how stories get picked reminded me of one of the last stories I worked on at Fox.

In January 2017, I was asked to launch an investigative unit for the Fox News Channel. It wasn’t unfamiliar work. Much of my early career was spent doing investigations, searching government records, analyzing financial documents, hidden cameras, stakeouts, stings, and the hardest and best part, getting the people who know the truth to trust you. Getting them to talk. I was told to find stories a few “degrees” off the focus. Events outside the media’s glare.

A simple way to do this is by finding stories that hadn’t been reported. Stories that sit, gestating, in places like court documents and military after-action reports. One enterprising young reporter began combing through court records in federal courthouses. Just not the ones in NY, DC, or CA. There’s bias in the media. The easiest one to compensate for is geography. We find stories where we are and too many journalists exist in too few places. The ongoing evaporation of local news means stories of corruption and wrongdoing too far, literally, from newsrooms in New York or Washington DC aren’t capitalized on because they aren’t found.

One court case we found turned into the first podcast I ever worked on. “Derby City Betrayal” explored a shocking tale of the sexual abuse of teenagers, police negligence, and federal investigations of the Louisville KY Police Department’s Youth Explorer program.

My contribution to finding untold stories or stories that deserved amplification was wandering in the places these stories hide, well, hide in plain sight. Once upon a time, you’d subscribe to dozens of local papers. They would come in the mail. You would read them. After you would need to wash your hands. Today, social media is the place for this. Anyone can post. One thing I’ve learned in 30 years of doing this work is that there is always a story to be found. Finding it is the challenge. A bit like mining for anything. Very much a “wheat from the chaff” endeavor. But when it pays off you do feel like you’ve struck gold.

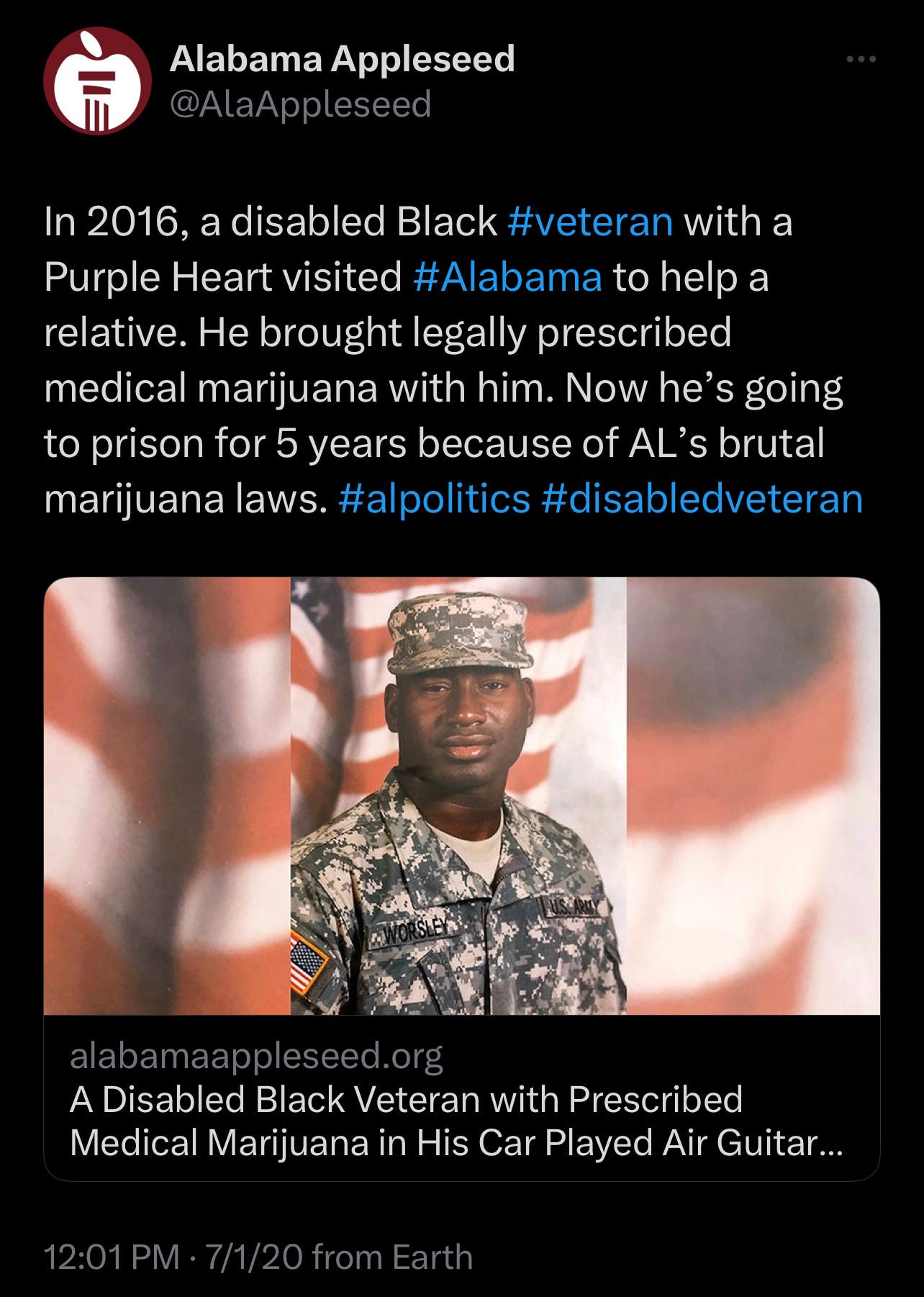

I found this particular story in July 2020. It began with a Tweet. An Iraq War veteran was serving five years in prison for possession of marijuana in Alabama, where the drug is illegal. The catch? The pot was legally prescribed in Arizona to treat his post-service issues like Post Traumatic Stress and Traumatic Brain Injury. His name is Sean Worsley.

The next catch? He was only driving through Alabama from Arizona to visit his mother in North Carolina. He was going to help her recover from a hurricane that had hit her area. The police officer began the interaction because his music was playing too loudly. I read the linked article from the Alabama Appleseed. It included facts like these, “According to an arrest report filed five days after the incident, [the officer] heard loud music coming from a vehicle and ‘observed a Black male get out of the passenger side vehicle. They were pulled up at a pump and the Black male began playing air guitar, dancing, and shaking his head. He was laughing and joking around and looking at the driver while doing all this.’”

I chatted with one of the reporters on my team. He didn’t need much guidance. His first story came out a few days later. One point we raised. Alabama respects the laws of other states, in some cases. This reciprocity extends to firearms. A concealed carry permit from another state is legal in Alabama.

There was more coverage, by Fox and many others. Then in November 2020, Sean Worsley was released. He had spent 10 months incarcerated. The Alabama Appleseed covered the news. In their article, there is a painful detail that I will let speak for itself. “Last year in Pickens County, where Worsley was held from March through September, a former sheriff was sentenced to 18 months in federal prison after he stole $400,000 money from the food allowance intended to feed inmates. To feed the inmates in his care, he defrauded a local food bank and his own church, taking almost half a million pounds of food at extremely low cost to himself.”

Sean was featured in an episode of Nova in 2021. You can watch that here. I recommend it. This tale is a small detail that painfully illustrates what the powerful in our culture can do to those without power. For me, it’s a reminder of what journalism does best. It lends power to the powerless. It helps put us all on a more just, noble, and prosperous path.