There are things you hear that just stick with you. What are the cliches? “It was seared into my brain” or something about words haunting you. It can be a painful thing, or a cruel thing, but this is about words of wisdom, or perhaps, it’s words from the wise.

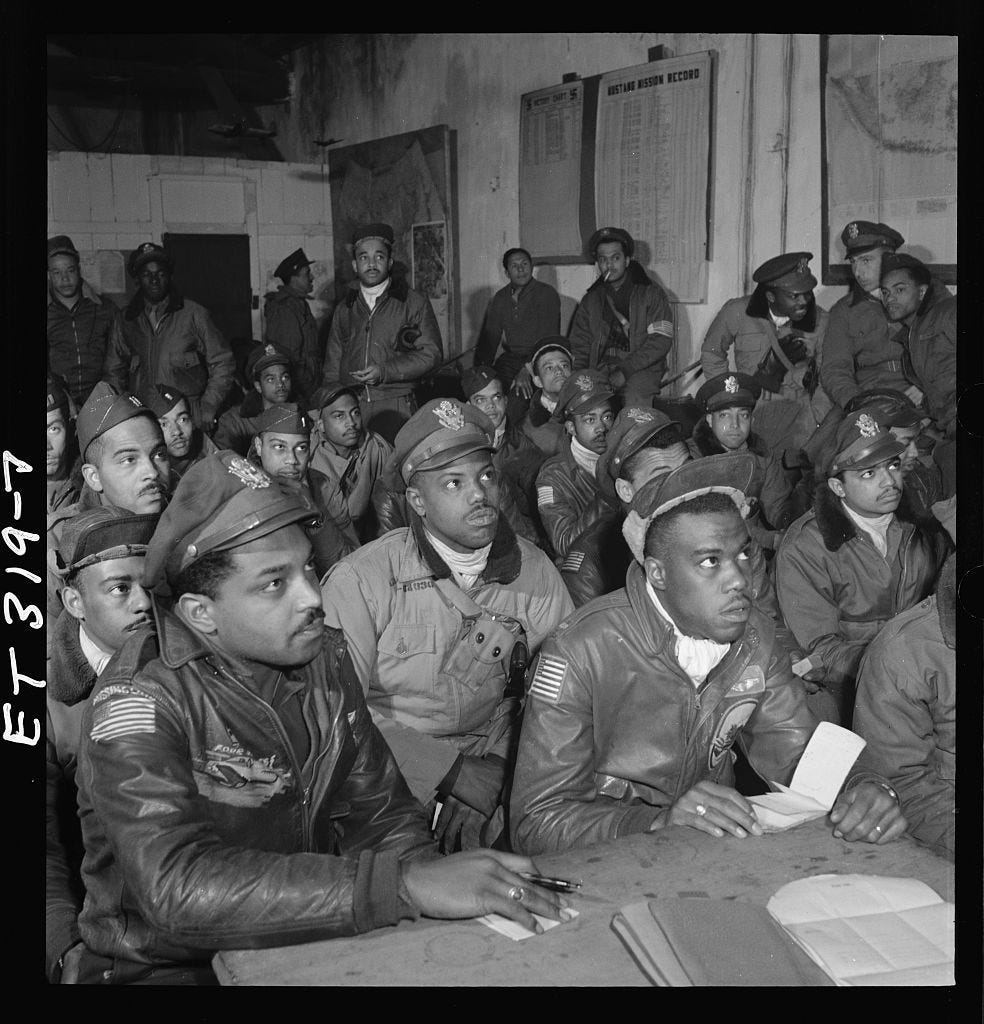

Almost 20 years ago I worked on a TV show about the Tuskegee Airmen.

The Tuskegee Airmen refers to a US military unit formed during World War Two, the nicknamed derived from it’s birthplace, Tuskegee, Alabama, and their jobs, pilots and support crew for an aircraft unit. At the time the US military was segregated, the Tuskegee unit was comprised of black pilots to maintain the segregation.

The men in this unit came of age in a time when lynching and racial violence were not just common, but celebrated and memorialized.

In 1939 there were just over 100 licensed black pilots in America. Getting the chance to fly or fight was no small feat. The US military claimed science demanded limiting the jobs black men might do. A 1925 Army War College study titled, “The Use of Negro Manpower in War” made claims like this;

Black men are “very low in the scale of human evolution.”

The “cranial cavity of the Negro is smaller than the white.”

“The intelligence of the Negro is shown in his inability to compete with the white in professions and other activity in peace time when mental equipment is an essential for success.”

“He cannot control himself in the face of danger to the extent the white man can.

“He has not the initiative and resourcefulness of the white man.”

“He is mentally inferior to the white man.”

“In general, the Negro is jolly, docile and tractable, and lively but with harsh or unkind treatment can become stubborn, sullen and unruly.”

The Tuskegee Airmen deified these claims, learned to fly and went to war and in North Africa and Europe. Their performance was exemplary.

But when the war ended the desire of many to return to normal came as a crushing blow to the Tuskegee Airmen. Of that pilot, Lee Archer said, “when I came home from World War II, after having flown 169 combat missions, I came home and the first sign I ever saw at the front of the gangplank said, ‘colored troops to the left, white troops to the right.’ Separated again.”

Pilot Charles Dryden came home from the war as well, consider what he witnessed. “There were German prisoners of war who could do things that we couldn't do. In our country. They could sit anywhere on the base, we had to sit in a segregated colored section. They could go up to the PX and have a meal that was off limits to us. I got so fucking mad. I couldn’t believe that our country would treat us like that,” he told me.

These words linger with me. They trigger thoughts about progress and justice and diversity. In those moments of contemplation I’ve connected a few dots.

The takeaway, things get better when you add more seats to the table. Things are better when the number of people involved in society grows. The widening of society to include a more diverse collection of citizens results in a more powerful nation, a greater nation than before.

Consider these milestones of progress. America became stronger after the The Civil War ended slavery. Woodrow Wilson resisted granting women the right to vote for years. It was the contribution of women to America’s World War One effort that swayed him.

After World War Two and the success of units like The Tuskegee Airmen the US Military desegregated in 1947. America was better for it. Almost 15 years later The Civil Rights Act took America another step forward. We were better and more powerful for it.

I moved to America as a English school boy in 1976. At my first school in the US, on the bus, I was “the funny accent kid.” I lost my accent in two weeks. Moving again, to Roosevelt Island in New York City, then again to the suburbs of Boston. In a couple of years another move found me in the New York City suburbs.

Moving as a child can be difficult. As the “new kid” I certainly faced challenges that, at the time, seemed punishing and unfair. But with the hindsight time affords me I see and feel differently about it. For all the difficulty it’s made me a person that likes people unlike me, places unlike mine. I prefer it diverse.

I wasn’t a terribly effective student, and I found it helpful to cast complex ideas into simpler terms. In history class I took to thinking of a particular country as a person. The history of a nation are the experiences a person might have. All of those experiences, or events, serve to create the current reality and personality of a nation. Its leadership and people all impacted by the country’s shared history.

Likewise, placing the idea of diversity and inclusion in a personal realm helps me see how those acts make us better as individuals and a nation. But, I need to be clear, this isn’t a comparative tale. Meeting men who endured what the Tuskegee Airmen did, only reminded me of the power of diversity in my life. They opened my eyes to the power it had granted me and the power we have gained from it as a nation.

The bravery they showed is hard to comprehend. They wanted to fight and perhaps die to defend America, all while America was producing studies that viewed them as “very low in the scale of human evolution.” If you read the cruel, terrify and grotesque history of segregation, lynching and violence you gain some sense of what they overcame to face death in World War Two.

Why did they do it? I’ve remembered a fairly common theme among the Tuskegee Airmen I met. They were happy, upbeat, optimistic. I remember sitting in Charles McGee’s home near Washington DC as we talked about how you endure difficult things, how you succeed in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. He was clear, you can’t be deterred, you simply have to take the opportunities that present themselves. Even in the worst of situations there is something you can do, however small, to improve your circumstance.

After Lee Archer recounted coming down the gangplank to a sign separating him because of the color of his skin he said something else that’s has stayed with me. It speaks to the importance of seeing the silver lining among the clouds.

“You get these punches in the guts every once in a while and it was should make you hate everybody, but you then you had to kind of balance it with all the good guys from the other side that you’ve met. And if you’ve got any reasoning power at all you realized that this is certain individuals.”

You can hear more about the Tuskegee Airmen here.

Author’s Note: Over the course of my journalism and television career I’ve traveled the world to document the actions of individuals during warfare. I’ve met and interviewed in some capacity 100s of veterans, the actual number might be in the 1000s. This is an ongoing series to memorialize my experience and further record remarkable acts and attitudes the worst of humanity can inspire.