It is a well-worn and used line, “all good things come to those who wait.” It, like so many well-known sayings, comes from a poem.

Do you know which one? Who wrote it? What it means? Put thoughts on that aside for now. Be patient. The answer is on the way.

But first, a wait.

What is patience?

Patience is remaining calm when everything seems to be, or actually is, going wrong. It is being composed in the face of difficulty. It demands self-control. It requires emotional intelligence. Patience allows us to endure delays without impulsive reactions. Patience is a form of wisdom. A wisdom that tells us progress and success often requires time, perseverance, and calm.

This is not the same as paying attention. Much is made of the way modern life and technology dilute our ability to pay attention. Much of this concern is warranted. But it is complicated. There are excellent reasons humans are easily distracted. One wouldn’t want to dismiss the rustling in the bushes for a bird when it is, in fact, a lion.

Danger lurks.

My thoughts on patience are born in the modern age and how that era has changed us, how it is changing us. The risk that change creates is unlike any in our history.

So, when I say “the death of patience,” I mean the loss of an element of our collective wisdom.

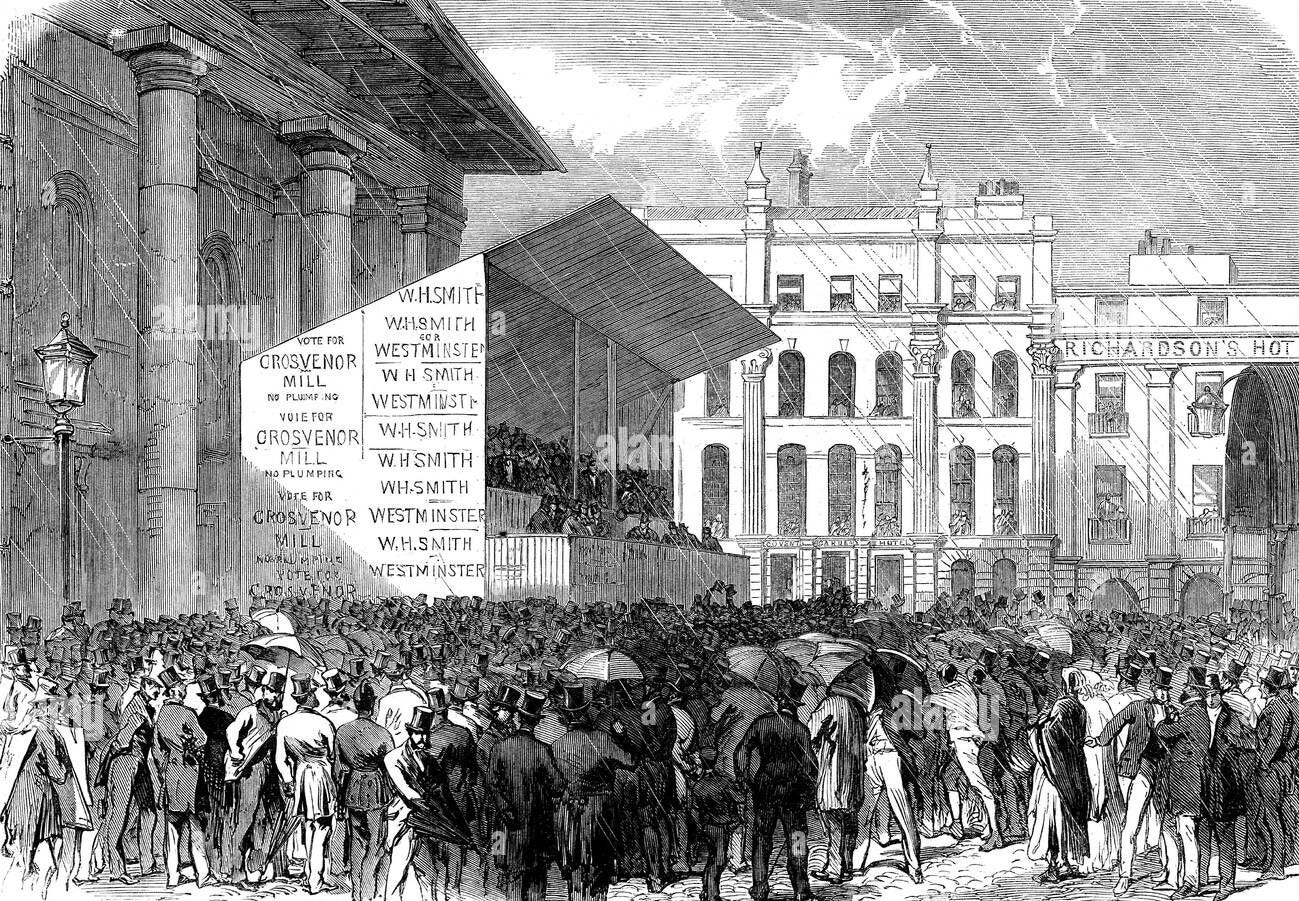

As a starting point, we will take the Industrial Age. I like to think of it as the Age of Mass Collaboration. Masses of people were aligned with advances in industries like manufacturing and construction. Great and dynamic designs came to life.

The dilemma with this progress was well observed at the time. Consider Charles Dickens, a chronicler of the Industrial Age. In Bleak House, he wrote of London’s inhabitants in the mid-1800s like this, “ jostling one another's umbrellas in a general infection of ill-temper.” We know this scene. Everyone is in a rush not to be where they are.

He was not alone in his concern about the mood and pace modernity and industry had inflicted on his fellow humans. Fredrick Engles noted in The Condition of the Working Class in England, “Their tempers are irritable, their manners harsh, and their mutual intercourse is characterized by a certain brutalization. This brutalization is the result of the oppressive conditions in which they live.” Regardless of politics (he was one of the first two Communists), his observations of the working class, the majority, stand as a fact for him to represent.

As the decades following these observations unfolded, we became capable of doing much at a pace and speed that reshaped the world. Sail gave way to steam on the seas. Horses and feet were usurped by cars and trains. Electricity and artificial light assaulted the daily rhythms of the sun and moon and won.

And the airplane.

In "The Shape of Things to Come" (which I guess is what I’m on about), H.G. Wells wrote of the Atlantic Ocean, “the greatest barrier left between the continents, and to see it swept away, to cross it in hours instead of days, was to many minds the most impressive of all the triumphs of science."

A triumph of science over geography. Science and the advancements it made possible created time—the ability to be somewhere else sooner than before.

Patience has always been finite. One of my favorite myths about the so-called “good old days” revolves around this photo.

I’ve written about it before, and it's the basis of my 18-month rule. That’s the maximum window for action before the population in our time gets restless and loses interest.

In this case, during World War Two, FDR authorized the publication of this image—the first ever depicting Americans dead on the battlefield. He was concerned that the American public was losing interest in the war. Unaware of the price being paid for their freedom. They were ready to be done. To move on. But without their support, the war couldn’t be won.

This was the attitude of the so-called “Greatest Generation.” Impatient and ready to be done with it all. The photograph was published in Life Magazine in September 1943. Less than two years after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor dragged America into the war.

There are moments after that that stand out.

Among them is JFK’s line that “within the decade,” we would put people on the moon. I can’t imagine a politician being allowed to utter those words today. I can’t imagine them wanting to. Who is going to wait as long as ten years for something? Who would dare ask them to wait?

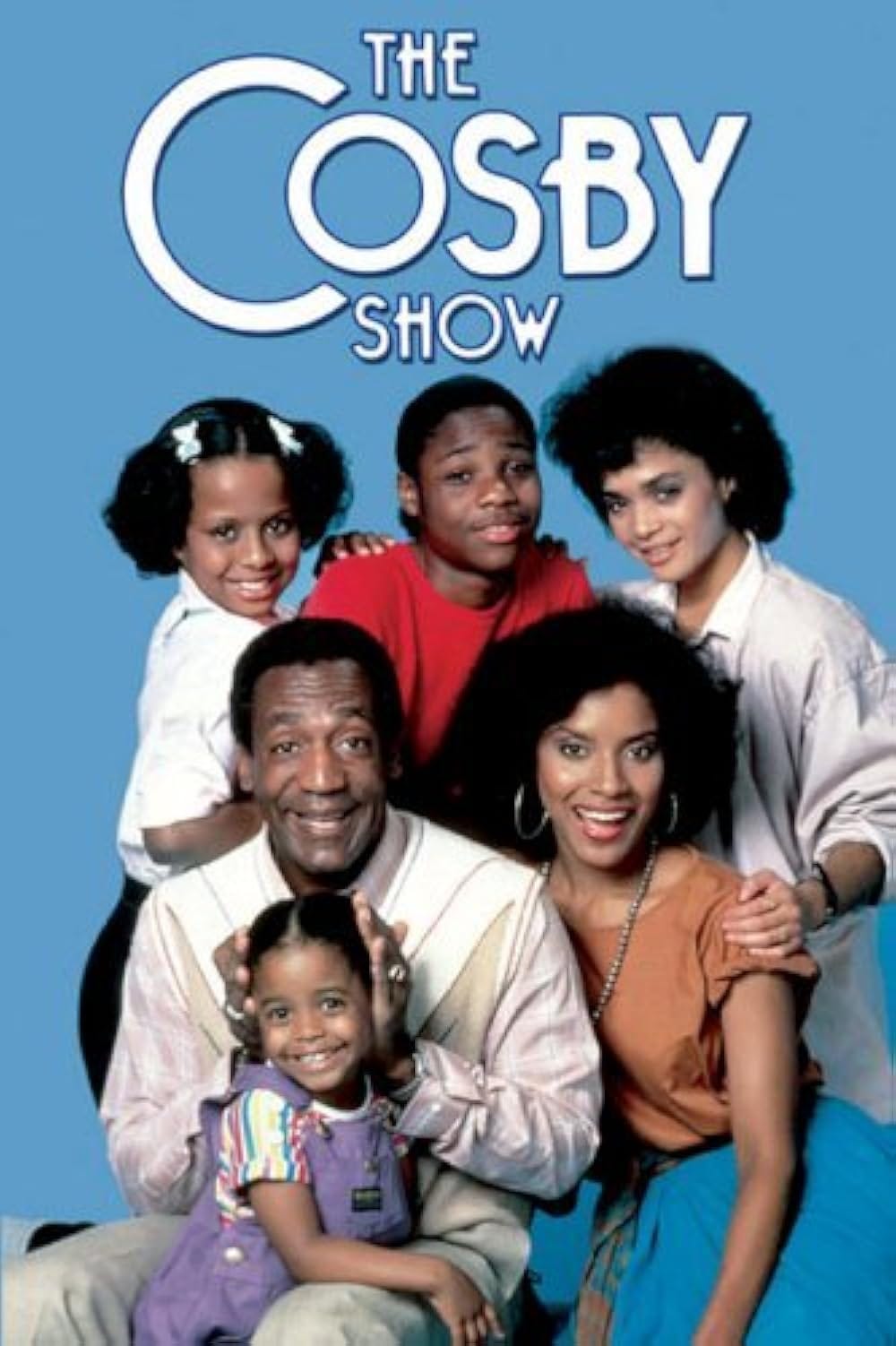

I can pinpoint the beginnings of my observations on patience. Of this distortion of what it takes to succeed, of the work and time hard things require, to a TV show—"The Cosby Show," to be precise.

In the 1980s, television sitcoms like "The Cosby Show" presented complex problems resolved within a 30-minute episode (22 minutes without commercials). The topics tackled in this tidy time? Underage drinking, money management, dyslexia, and dropping out of college. This condensed format does not accurately depict what is required to tackle such things. But we loved it.

A point; stories need ends. These shows had and have great value. in lighthearted and serious arenas. This format isn’t sinister; this is more about an unintended consequence wrapping it all up with a pretty little bow.

According to TV viewing statistics, ratings, in the mid-1980s, Americans watched about seven hours of TV daily—roughly a third of their time. Throw in six or so hours of sleep and it is an even more significant percentage of our lives.

With the increasing pervasiveness of TV, including cable, entering the fray in the 80s, I can’t help but think that this format, mirrored by many other shows, subtly shaped our expectations of what life should be like. It told a story of complex issues that could be solved quickly and done so with humor. Often in a single conversation.

This portrayal of life created a perception that hard work and time-consuming efforts could be bypassed. The people on TV, the examples held up to admire, the famous and the celebrated, even though fictitious, can achieve quick, successful resolutions. We are left wanting that as well.

If I can’t? I am failing.

As the internet began to proliferate in the 1990s and 2000s, the volume of choices and the immediacy of information further altered societal expectations. The rise and the convenience of early online services like AOL Instant Messenger or Napster contributed to a cultural shift where waiting became more of an inconvenience than a natural part of life.

My television career began in 1992, actually, 1989, if you count summer internships. Television is all about gaining people’s attention and keeping it. It is about judging what is just enough time. In a way, it's about judging how patient you can expect people to be. It demands or entices their patience by telling a story well. To illustrate my point about patience, I will use an anecdote.

As it does today, data drove a lot of things then. One of my vivid memories involves reviewing minute-by-minute ratings for a show I worked on in 1999. I’d produced a two-part segment for a network program on a military competition called The Best Ranger. The parts were separated by three or four minutes of commercials, and one of the significant considerations while writing it revolved around making sure people returned for part two.

I can see the ratings graph in my mind's eye. Part one ends, and the ratings plummet. I mean off a cliff. Among my first thoughts? “No one watched these commercials.” Happily, they returned for part two, and the ratings increased for the remainder of the segment. I had hooked them.

When you do it well, you cast a sort of spell that makes people forget time. They don’t even realize they are waiting patiently. One of the finest compliments a TV anchor ever paid me was when I was told a segment was beautiful and “so long!” “What was it? Seven or eight minutes?” they said. I smiled. It was 16.

The arrival of services like Netflix and platforms like YouTube in the 2000s layered a new burden and promise. Netflix began by removing the need to be patient as we traveled to the store, to be patient as we looked for a film, and to be patient when our first choice wasn’t available because someone else had taken it. Then, the offer of instant streaming of movies, shows, and video content further conditioned people to expect immediate gratification.

This trend only accelerated in the 2010s and 2020s. Social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram offer real-time updates and instant feedback through likes and shares, diminishing the need and apparent usefulness of patience. They are also designed to keep us in their realm. The addictive quality of the well-crafted algorithm is currently more powerful than a clever turn of phrase or promise of a grand finale.

Recent research highlights people's lack of patience.

A Google study found that 53% of mobile users will abandon a site if a video or webpage takes longer than three seconds to load. You wanted it, but it took over a few seconds, so half of us gave up.

In 2012, a study found that people are less willing to wait for more significant rewards. Instead, we opt for smaller immediate rewards. They call it temporal discounting.

In the 2020s, published research explored how the instant gratification culture fostered by social media and online platforms leads to compulsive behavior. It diminishes our ability to wait. Most concerningly, it reduces our capacity to engage in long-term planning.

These conveniences aren’t without value. But convenience comes with a cost. It has led to frustration and abandonment when things don't happen instantly.

The fact is that life isn’t just about the moments of satisfaction; it's about the moments in between—the waiting, the process, the time it takes to work through challenges. These intervals are vital and often complex. Whether it’s settling an argument, understanding a nuanced problem, or simply allowing for the natural progression of events, these periods of patience are crucial for meaningful outcomes.

Patiently navigating issues, reflecting, and engaging profoundly helps build more robust solutions and relationships. Yet, as our ability to wait diminishes, our capacity to handle complex challenges effectively falters.

Some may see the decline of patience as a byproduct of our desire-filled, fast-paced world. But the danger becomes primal to our existence and civilization. It’s a trend that requires mindful attention to ensure we don’t lose the valuable skills and benefits of waiting and working through challenges. If our ability to wait and focus diminishes, the broader societal consequences will be profound. It will impact everything from interpersonal relationships to how we approach complex problems in the future.

As we look toward the future, the long-term effects of growing up in an "always-on" instant gratification culture are worth considering. It is well established that the human brain isn't fully developed until age 25. What will a generation that reaches adulthood look like in a world where every desire can be fulfilled immediately? If only temporarily. Or until the next dose hits you.

How will they work, govern, and solve problems that require sustained effort and attention? The adage "We get the leaders we deserve" may take on new meaning in a society where patience is in short supply. An impatient generation that cannot occupy its mind without constant stimuli may well deserve leaders who prioritize quick fixes over long-term solutions, shining new distractions in our faces while sweeping real issues under the rug. The implications of this shift are profound and warrant careful consideration as we navigate an increasingly digital world.

Consider some things we value or rely on and whether the patience to wait would exist today.

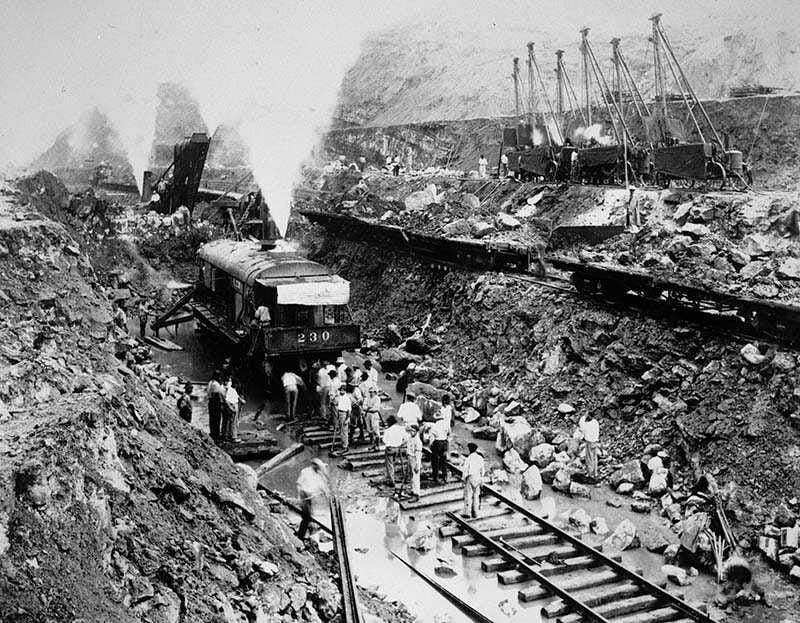

The Transcontinental Railroad took about six years to build and another twenty to plan. Would we wait? Could we wait?

The Panama Canal. First, the French and then the Americans toiled to complete this marvel of engineering and commerce. It took three decades of work. Would we wait? Could we wait?

And the wait is over; “all good things come to those who wait” is from the poem "Retribution" by Violet Fane. Here it is in full. It’s short—no need to be patient.

Retribution

"'Ah, all things come to those who wait,'

(I say these words to make me glad),

But something answers soft and sad,

'They come, but often come too late.'"

The poem is about waiting too long. So long that the arrival of what we sought is of no good. It is “too late.” What good is patience, then?

We stand at the intersection of patience and its decline in a world where waiting is both a virtue and a vice. "All things come to those who wait," as Violet Fane wrote, but as she warned, they sometimes come too late. This truth points to a delicate balance. Patience may be a virtue, but to be too patient is a vice. To wait endlessly can mean squandering opportunities and letting chances slip away until they no longer exist. The world may turn and pass us by, leaving us behind, clinging to the hope that things will come in their own time and that the reward is certain if only we endure.

But as technology alters our very minds and behavior, this complex riddle evolves. It is a dilemma from which we cannot turn away.

When a civilization can’t bear even a moment's pause, it risks becoming shallow and reactive, valuing only what is immediate and fleeting. The ability to see beyond the next instant fades; the skills needed to build, create, and solve complex problems diminish. The strength to endure, recover, and hold hope through uncertainty is lost.

What happens if we cannot wait?