One of the more interesting parts of working on television or in journalism is that it grants you access to places and people. This isn’t a critique of power and influence. It’s about fun stuff you get to see and experience. Well, not just fun stuff, but we’ll start there.

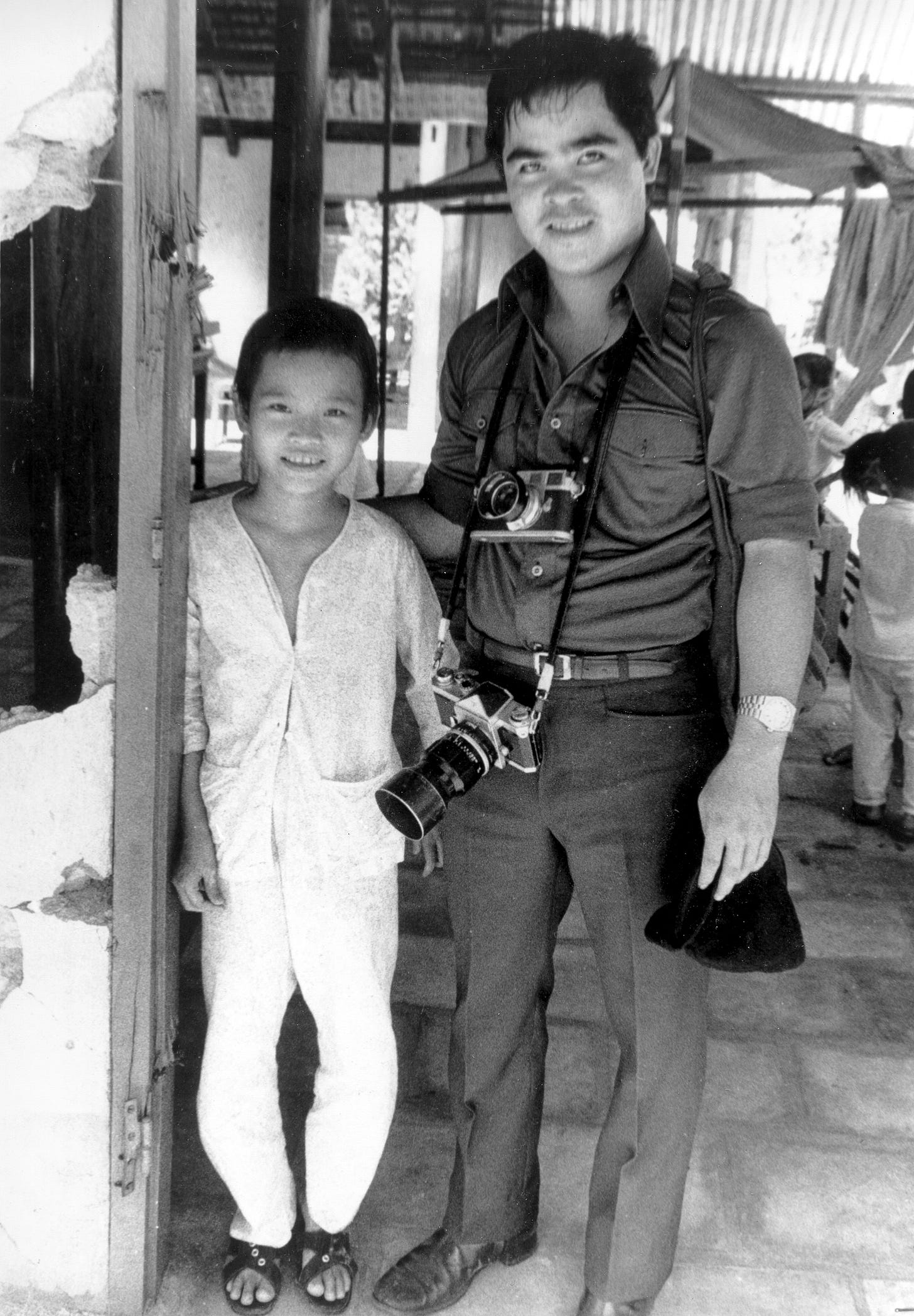

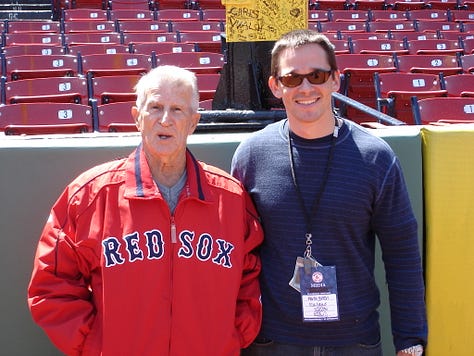

Like the time officials at the US Air Force Museum, in Dayton Ohio, let me inside the B24 Liberator on display. In The Philippines while trying to sleep in a hilltop artillery base I was startled by a US Army Green Beret patrolling the camp. He appeared out of the dark. I watched as he wandered, seemingly without purpose. When I asked about that he replied, “routine is deadly, stay unpredictable.” On the safer side you pose with Red Sox legend Johnny Pesky. The yellow foul pole named after him your backdrop.

Then there are the times you get to meet the people who were at the center of attention. In this case the person captured in that photo and the person who took it.

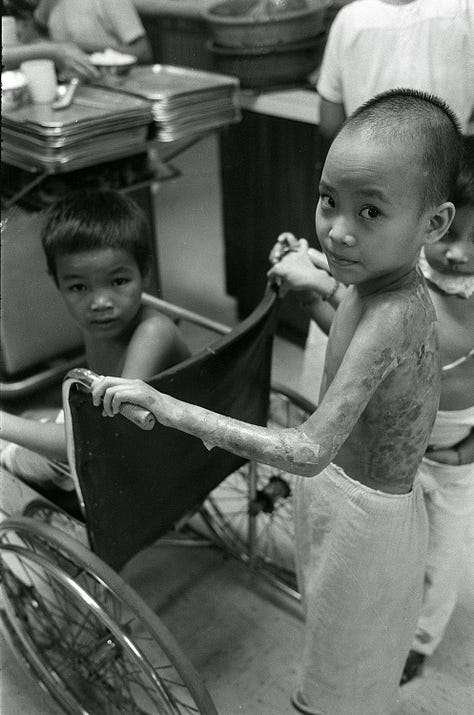

It is what gets called an “iconic image.” One that captures not just a millisecond in time, but also the mood and reality of an era. Kim Phuc was nine years old in June of 1972 when her village in Vietnam was hit by an airstrike. The planes dropped highly flammable napalm. The resulting fire burned Kim and many others severely. As she ran away from the village a young photographer raised his camera and did his job.

Nick Ut was only 22 years old that day. His photograph would travel the world and win the Pulitzer Prize. It was also greeted with skepticism by President Nixon. Shouts of “fake news” or assaulting the messenger are not new.

I grew up in a news household, piles of papers on the kitchen table each morning. I had seen this photo again and again, knew its history and now here I was with the person in it and the person who took it. We all met a little over 30 years after the day those bombs were dropped and that photo was taken while I was working on a television show.

Nick Ut, told us this about that moment, decades earlier, "I saw a bomb fall down, right away. And another bomb, napalm, explodes.” He continued, “I hear all the children running. Then I took her picture, four or five photos."

Kim recalled the moment this way, “suddenly, I saw the fire everywhere. And then, the fire just burn off my clothes. I saw the fire. I keep running and running. And I scream out, ‘Too hot, too hot.’ The soldier gave me some water to drink. And then he tried to help me. He pour the water over me.”

After taking several photos Nick put Kim and others in his car and drove to a hospital.

At the hospital help was not quick. Nick told us the doctor said, "they don't have time to take care of Kim." He pushed back, telling them, "I'm Bao-Chi, I'm media. Please help her. I don't want her to die. You guys will have more trouble. You'll have the front page tomorrow about you."

Kim told me she was so very grateful Nick saved her life. But we also wondered if she was ever angry the photo was taken. She said in reply, “sometimes I say I wish that picture was not taken. I hated everybody." Kim spent 14 months in the hospital recovering.

She told me that her conversion to Christianity a decade after the photo was taken led to a sense of peace falling over her as she was, “freed” from the, “hatred, anger and bitterness.” Then, in 1992, while traveling from Moscow to Cuba she defected as her plane refueled in Canada.

Since then she has founded the Kim Phúc Foundation. The organization, “exists to help heal the wounds suffered by innocent children and to restore hope and happiness to their lives.”

The day we spoke was decades removed from the pain and horror of that day. That time afforded the glorious benefit of hindsight, or perspective. Kim told us, "I can use that picture, for good. To promote peace. Let people know, how horrible war can be.” She continued, “we cannot change the past. But with love, we can heal the future and then, I realized that picture became a very powerful gift for me."

Imagine looking at a photo of your younger self, in pain, likely near death, in the midst of a war zone, and considering it a “gift.” I remember that moment in the interview, it made the final edit. I considered the hardships we all endure. We have the cliches, whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger sorts of stuff (apologies Friedrich).

It’s very easy to say, to offer those words of encouragement. But when you are in the moment, be it as unimaginably horrible as Kim’s or more simple daily trials and tribulations we can lose hope. That’s what stayed with me. A further lesson in giving it time. It’s very difficult to understand why something dreadful happens while it is happening. Take your time, be patient with yourself. Kim found a purpose, a gift, in that dreadful day and the image of it. If she can do that, I can with my own valleys. I hope you can as well and like Kim come to realize, “we cannot change the past” but, “we can heal the future.”

You can learn more about Kim and Nick here.