Are you “set in your ways?”

Changing people’s minds is hard. We learn things, and they sit with us and become what we know. Even when they aren’t accurate, we hold on, anchored to an untruth or simply an incomplete understanding.

Anchoring bias describes the human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered and learned. In the context of news or media, consider this scenario. If the first reporting of a political scandal estimates $10 million worth of wrongdoing, we set this as the anchor. All new information must topple it. Even if further investigation reveals the actual amount is significantly lower, say $1 million, our perception can remain skewed by the initial higher figure.

We dig in our heels.

We bury our heads in the sand.

We all do it. Even if we turn a blind eye or ignore our bias and ignorance.

Simply put, the first version of events that we hear has a tendency to become the king or queen of the hill. Any new information needs to knock that first impression from the summit of our minds. The hilltop comparison is apt because this is a tale of two hills—one you have probably heard of and the other you almost certainly haven’t.

The Battle of Hamburger Hill was a fierce and controversial engagement during the Vietnam War. It occurred in the rugged, heavy jungle of the A Shau Valley from May 10 to May 20, 1969. This battle saw U.S. Army and South Vietnamese forces launching several assaults against entrenched North Vietnamese Army troops on Hill 9371, known locally as Dong Ap Bia or “the mountain of the crouching beast.”

The hill was taken but at a heavy price. 10 days of fighting left 72 Americans dead and over 300 wounded. Our South Vietnamese allies suffered 1500 casualties. Then, almost immediately, the hill was abandoned. That left many wondering what the point of it all was. Among them a Senator from Massachusetts.

On May 20th of that year, Ted Kennedy stepped onto the Senate floor to address the controversy. He said in part, “The assault on ‘Hamburger Hill’ is only symptomatic of a mentality and a policy that requires immediate attention. American boys are too valuable to be sacrificed for a false sense of military pride.”

Hamburger Hill wasn’t the last straw, but it was one of the last when it came to public and political support for the war in Vietnam. On November 3, 1969, President Richard Nixon went on television and explained that the United States would no longer lead the fight against the North Vietnamese. Nixon looked into the camera and said, “In the previous administration, we Americanized the war in Vietnam. In this administration, we are Vietnamizing the search for peace.” The search for peace would take years.

Hamburger Hill became emblematic of the Vietnam War's brutality and the futility of such engagements; it also serves as a convenient end to the story of the war. Vietnam was a war in the 1960s.

If you ask ChatGPT or another AI about the last major battle of the Vietnam War involving US Troops, you get a clear example of its “anchoring bias.” You get replies like this, “The last major battle involving U.S. troops in Vietnam before the policy of Vietnamization took full effect was the Battle of Hamburger Hill, or Hill 937.”

It isn’t just the so-called hallucinations of AI that conceal the truth. The ten-part Ken Burns and Lynn Novick documentary on Vietnam, which spans 18 hours, also takes 1969 and Hamburger Hill as the moment of departure for US Troops and their combat role. You get the sense that the real war, the fighting and dying, has ended. But this is by no means accurate. It isn’t even close. My own relearning, or unanchoring, played out over a decade ago, and it began with Sports Illustrated.

Bob Kalsu was an All-America lineman out of the University of Oklahoma. After his rookie season with the Buffalo Bills, he interrupted his playing career to fulfill his commitment to the Army. He arrived in Vietnam in November of 1969, the same month Nixon said America was done.

Kalsu was killed in July of 1970, not much more than 10 miles from Hamburger Hill. He was the only American pro athlete from a major sport to die in Vietnam. Kalsu is the story of one man, but it opened my eyes.

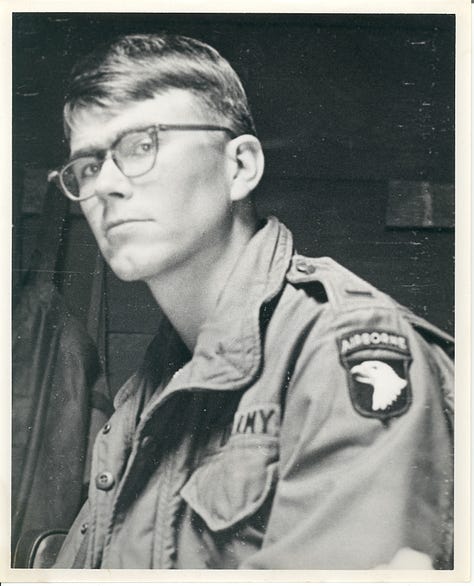

I learned that he was killed at a Fire Support Base or FSB. Like the troops at Hamburger Hill, Kalsu was a member of the 101st Airborne Division. This unit is probably anchored in your memory because it is the focus of the book and TV series Band of Brothers. This base, or FSB, was named in a tribute to the unit’s origins; it was dubbed FSB Ripcord after the name for what a paratrooper sometimes pulls to deploy their parachute.

John Kasich and I did a segment on Kalsu, but learning about him and this virtually undocumented battle during the waning days of America’s war in Vietnam had me hooked. I went down the rabbit hole. I found another band of brothers.

I was able to do another TV segment on two men who met on the battlefield around FSB Ripcord. They met when one saved the other. They had never met before and didn’t meet again until we reunited them over 30 years later.

Then, I set my sights on doing a documentary about the battle. That meant learning a lot more about why FSB Ripcord even existed. The idea was pretty simple; why it was being carried out is a bit of a mystery. Why risk more Americans in the open jungle after the politicians had said, “Let's bring the boys home,” and started to do that?

The premise behind establishing this base in the remote A Shua Valley was grounded in interdicting North Vietnamese supplies as they flowed south along the Ho Chi Minh Trails (sidenote on anchoring, it should always be written trails, plural. This was a vast network of trails and roads, not some singular single-track path like the Appalachian Trail.).

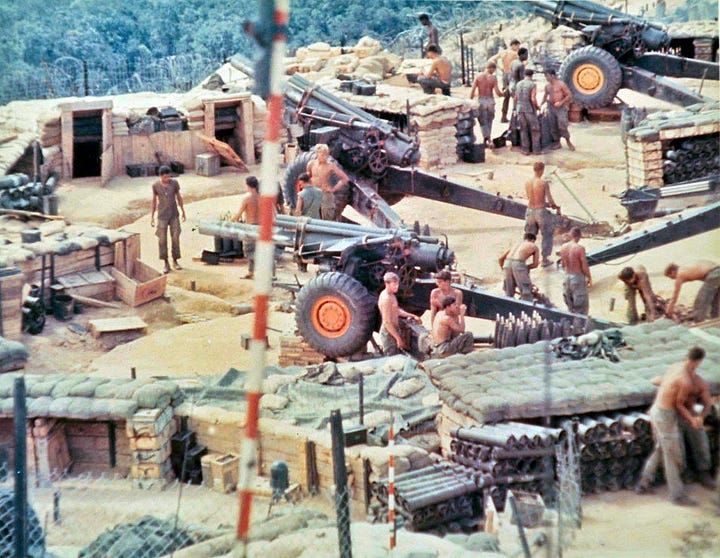

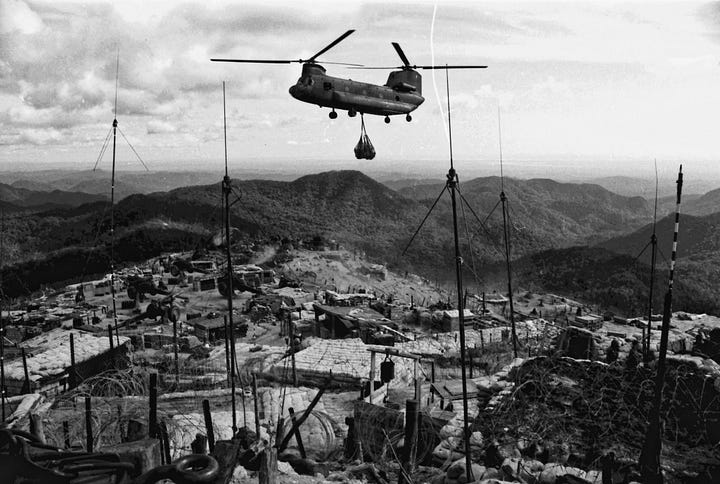

Ripcord was large and well-armed, as the word Firebase suggests. It had two six-gun artillery batteries, which supported the infantry as they moved through the jungle, seeking out the enemy. As I was told, the idea was that with America leaving Vietnam, the higher-ups wanted to put one last dent in the enemy and help our allies in the south out. However, given the ongoing withdrawal of troops and other complex issues facing American units, most people I spoke with scratched their heads over the risk-reward proposition of the plan.

When I did my research, only one senior commander from the unit was still alive. He didn’t want to talk about it. As my research unfolded, I learned the battle was subject to a press blackout. I was told of a helicopter full of reporters that came into land. As it approached, the pilot turned away. Over the radio, he was told he would be fired on. The press wasn’t permitted.

Likewise, the Army’s own film and media teams had collected scant content or documentation of the battle compared to others earlier in the war. Searches at the National Archives and other repositories weren’t fruitless, but they did disappoint. In the world of TV, it's hard to tell stories about things without pictures. I had a similar experience doing a television program on The Tuskegee Airmen. The Army didn’t do a great job of documenting their exploits. The PR headache anticipated if the public learned about black men flying was deemed a problem.

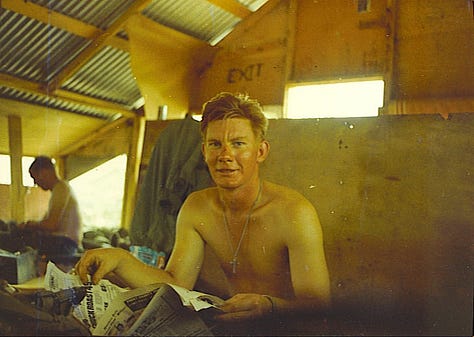

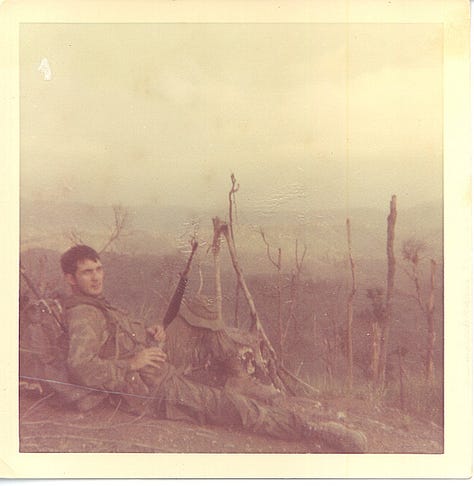

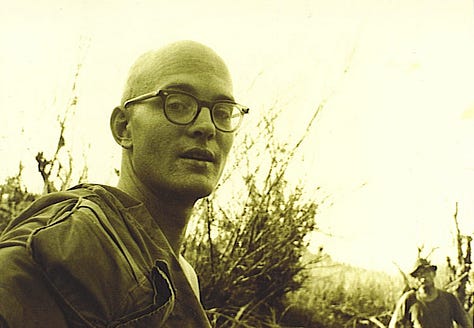

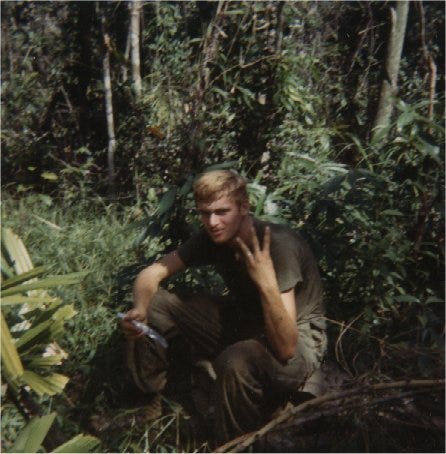

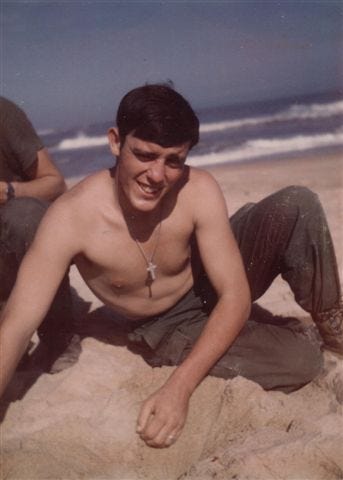

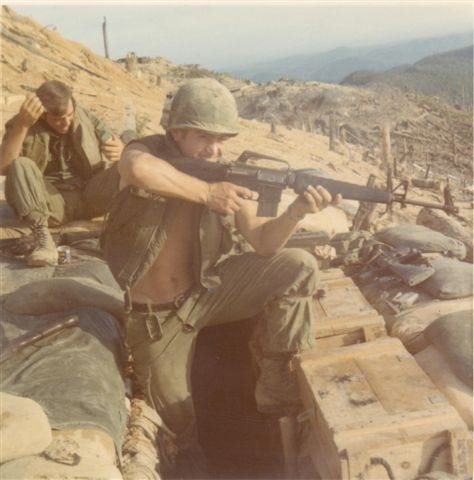

In research terms, this absence is a blessing and a curse. Getting material like film and photos from the National Archives is pretty straightforward. When there isn’t anything to glean from its holdings, you turn to people who were there and ask as many as you can what photos or film they might have. That is a blessing because it forces you to find and speak to as many people as possible. Men who fought in a forgotten battle are hellbent on making sure the dead are remembered.

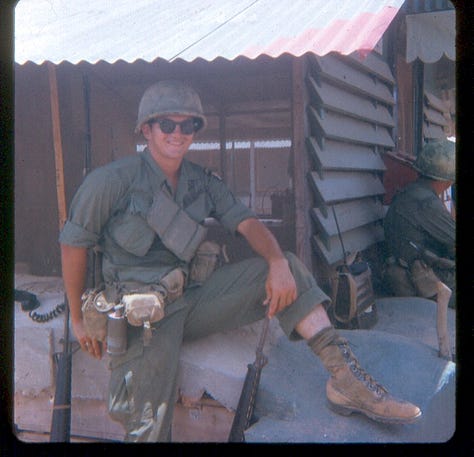

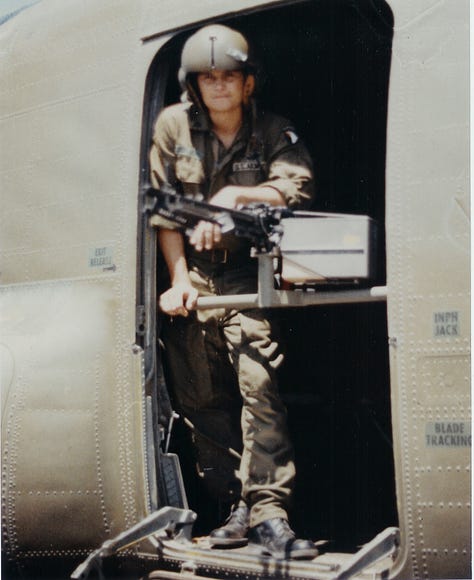

The battle for Ripcord lasted just three weeks. Or about twice as long as the Battle for Hamburger Hill. In the end, 75 Americans were killed, including many of the men in the photos above.

Like Hamburger Hill, Ripcord was evacuated immediately when the battle was deemed over. American planes bombed the site to deny the enemy anything of value. Another hill fought and died for and then abandoned. But this time, no senator gave a speech.

In 2004, I completed what I guess is my Ripcord Trilogy. We aired an episode of War Stories on the battle, which you can watch here. Over the next few years, I learned what happens when people feel like they are finally seen and honored. I learned what happens when the slight they have endured is lifted. Much is made of the way Vietnam Veterans were treated when they came home. I have seen that pain diminished. Their warm embrace, literally and figuratively, is a point of professional pride that makes my heart swell. I’m a proud member of the Ripcord Association.

Over a decade after it aired, I enjoyed lunch with a few veterans of the battle. Afterward, standing on the streets of Manhattan, they heaped praise on me for the work I had done. I’m always sheepish in those moments. I make the mistake of blunting compliments sent my way. But they would not let me; I can feel that moment on the corner of 47th Street and 6th Avenue.

Finally, there is hope, I guess. After correcting ChatGPT a number of times over a few weeks, and just before posting this, I asked again, What was the last battle fought by predominantly US troops and units during the Vietnam War? It’s answer, “…that would be the defense of Firebase Ripcord. This engagement took place from July 1 to July 23, 1970, and was part of a larger operation called Operation Texas Star.”

If machines can learn, surely we should seek to keep pace.

It’s common for hills to be designated by their height in meters; in this case, the mountain is 937 meters high.

Great photos, surprising what you can find!

Just read this. It's a good summary of the campaign on Ripcord although in truth it started all the way back in March 1970. I'd like to know who the people are in the photos.